Every single story, and perhaps every single work of art, has a frame. The frame is that which demarcates the “inside” of a work from the outside, the physical and psychic boundary that contextualizes the work. The frame is what tells you that the content of the Mona Lisa is the lady and the background, not the white wall behind her.

These frames are what the philosopher Jacques Derrida called parerga (singular: parergon). Derrida points out that all our standards of aesthetic judgment presuppose that we naturally know the difference between what’s inside a work and what’s outside a work, but in fact, it’s a pretty messy distinction. The parergon, he said, mediates (in an unstable way) the inside and the outside, fading into the background even as it clarifies the borders between inside and outside.

Most importantly, he highlights, a parergon is linked in an indissoluble way to the ergon (the “work” itself). A paraergon is a parergon not merely by virtue of exteriority (a frame isn’t a frame just by virtue of being outside the painting) but because it has an “internal structural link” to a “lack” in the ergon. That lack is nothing less than the very “lack of a parergon, of drapery or columns which nevertheless remain exterior to it” (in this context, “drapery and columns” refers to the sculpted curtains or columns etched into the wooden frames around paintings).

This is all to say that any work, painting or literature or game, can’t just be floating in space. We need a parergon to help us define what it is, why it’s here, and what we should do with it.

Magic’s March of the Machine was a complicated set—mechanically, yes, but also stylistically and narratively.

The story, whose main episodes were penned by K. Arsenault Rivera and whose ten side stories were written by a bevvy of other web fiction all-stars, was the most voluminous Magic narrative of the last several years. As it often goes in the Magic Vorthos community, the reception started positive (check the first Reddit threads sharing the web fiction for proof!), became mixed (check the later threads), and after the fact tended to homogenize into very specific feedback (check any thread about MOM on the Vorthos subreddit). The complaints: there was too much content; the Phyrexians seemed to lose too quickly; we needed novels; we needed ten novels; we needed two more sets to tell this story; we need blocks to return; etc., etc., etc.

Personally, I loved it. I loved the poetry of Rivera’s work, and I loved many of the side stories (Miguel Lopez’s Ixalan story was a highlight). The stories, especially the early ones, sold how apocalyptic the Invasion was and how miraculous it was that Wrenn and Chandra saved the day. I hear the complaints, of course about brevity, and it’s true that you could fill a novel or short story collection with all the different characters who were involved and the depths of their responses to the Invasion (I strived for this in my…novella?…about Benalia and House Capashen). But I’m not endeavoring to defend the story—ultimately, it’s subjective, and I tend to be a pretty forgiving reader when it comes to Magic story, because I love the aesthetics so deeply.

I bring MOM up, instead, because I want to think about what it means to tell a story through game pieces—how directly you can do so, how well you can do so, and where you’re going to run into challenges.

Framing Play

The conceit of Magic is that you, the player, are a planeswalker. In this hallucinatory narrative frame, your cards represent spells that you, a superpowerful mage, can cast: your creatures are basically hard-light images drawn from your memories; your sorceries and instants and enchantments are spells forged in your own hands; your hand consists of the spells you can remember; and the deck is your mind (this is why, from a symbolic perspective, spells that draw you cards, like Brainstorm and Ancestral Recall and Consider relate to memory and the imagination, while spells that mill cards, like Thought Scour, Brain Freeze, and Syphon Mind register the loss of knowledge or memory).

This framing device is more than a little goofy and more than a little charming, but it’s faded away in contemporary Magic, in which sets have grown more cinematic in style. When we play cards from Murders at Karlov Manor, the impression is far less of an epic battle between rival planeswalkers and far more that we’re in the middle of the world, enacting or reenacting the scenes of a hypothetical film. As I wrote in my previous article, it’s a thoroughly unique and weirdly fascinating medium for narrative experience.

This narrative frame, the reenacted story, can often synergize quite well with Magic game design in ways big and small. Some of the most famous examples are Sagas; I won’t go into greath depth, because writers like Rhystic Studies and Jay Anelli have already done amazing work on them, but Sagas are great for their metatextuality: they represent the stories told in-world about the world, and their game mechanics reenact these stories. History of Benalia is a stained glass window representing Benalish history, and its mechanic effect is to assemble a small army of knights and buff them up, just as the historic Benalish would have done. The Phasing of Zhalfir saves your permanents from a future assault, but leaves the battlefield open for the Phyrexians to seize control. And so on.

But we know how lovely sagas are. What about cards that aren’t so explicitly narrativistic? March of the Machine has lots of cards like this that, I think, deserve some appreciation—because they reflect our understanding of Magic’s game-narrative.

Something’s Coming

There’s a cluster of cards from MOM that don’t rise to the level of “cycle,” but that do something truly interesting, as narrative pieces.

A strange symbol appears tucked into a student’s notes on magico-mathematical functions, but the student doesn’t remember writing it. A duplicitous fortune-teller finds his body marked with apocalyptic prophecies. Hints trickle through a rainsoaked city of a new street gang, one that nobody has seen but whose insignia is everywhere. Tiny herbivores, skittering between the legs of gargantuan beasts, munch on flora that they’ve never seen before. People in monasteries and stadiums and performance halls are distracted by the flurry of business-as-usual and don’t notice that that, without realizing it, their very bodies have begun to move in new rhythms, as though keeping time to a frequency resonating from elsewhere.

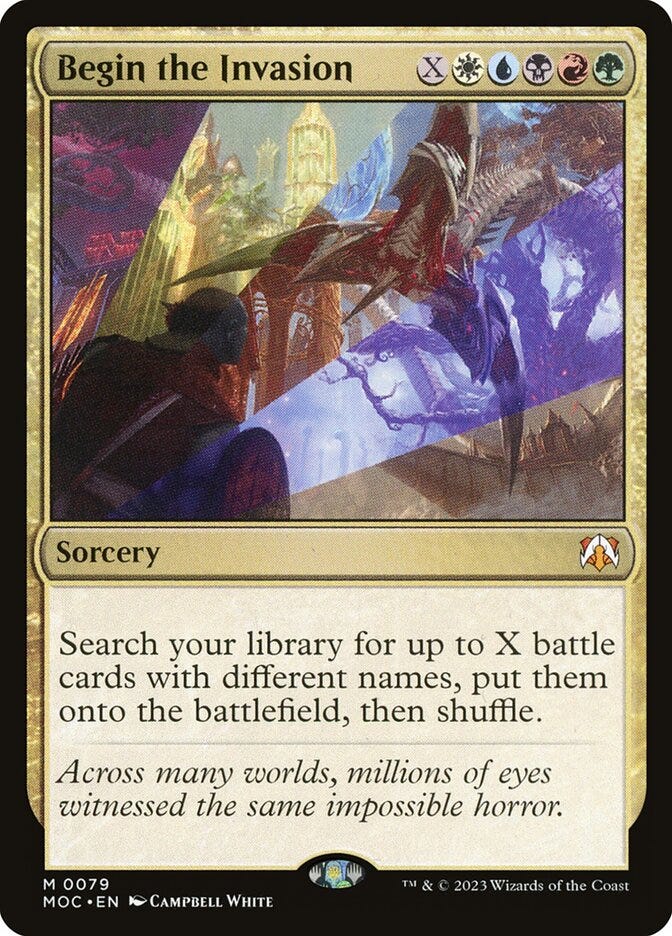

Portent Tracker says it all. “In the days before the invasion, the symbol of its perpetrator appeared in strange places all across the Multiverse.” And then: Begin the Invasion.

As individual pieces of art and storytelling, the members of this quasi-cycle work as haunting prelude to the Phyrexian Invasion. Like the first act of a horror movie, they introduce a world in which all seems well, marred only by one thing—one thing not just right, one thing that’s small enough easy to dismiss as nothing at all. One thing that promises the end of everything.

Except, as I argued in my last post, no Magic card ever works exactly like that. Magic story means not just the events the cards briefly capture, but a whole constellation of experienced realities they belong to: web fiction and flavorful cards, imagery and imagination, game previews and gameplay. This narrative is experienced not just through prose but through game pieces and their paratext.

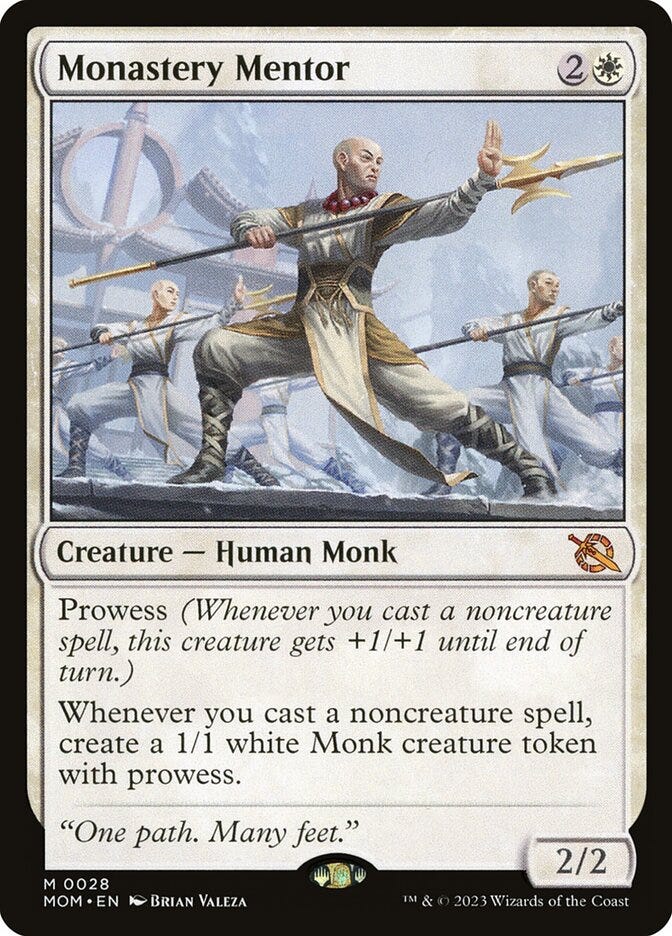

So what makes these cards so powerful is that their story content actually corresponds with the framing device—the game of Magic itself. These are all cards that (mana curve providing) can be played on turns 1 (Placid Rottentail, Omen Hawker), 2 (Nezumi Informant, Wary Thespian, Portent Tracker), or 3 (Monastery Mentor, Preening Champion, Furtive Analyst)—just as their art drops the first hints of the invasion, they are likely to be played in the first turns of the game. So too with their abilities: some, like Furtive Analyst and Placid Rottentail, stay vigilant for these new phenomena (and have vigilance), while others, like Nezumi Informant and Wary Thespian, gather scraps of what’s to come (just as the player uses their abilities to scry cards or draw from their deck).

But my favorite of all is Omen Hawker.

If you knew nothing about MOM or its background, you might be puzzled when your opponent first plays this odd card, this creature which taps to produce one colorless and one blue mana—what an odd combination of mana! And only to pay for abilities?

But the very next turn, the horrible realization arrives: your opponent plays any of the many 3-mana-or-less cards that Incubate—creating garish alien pods that, when fed with Omen Hawker’s 1U mana, burst forth hideous Phyrexian monstrosities. Or perhaps the card will pay the cost to transform Heliod, the Radiant Dawn into Heliod, the Warped Eclipse or Khenra Spellspear into Gitaxian Spellstalker. Or perhaps it’ll help pay for flipping Elesh Norn or Jin-Gitaxias, proclaiming their monstrous visions of reality.

From a gameplay perspective, Omen Hawker’s chances of helping the multiverse’s defenders are slim: of the 98 MOM cards that either Incubate or have mana-activated abilities, the vast majority represent the Phyrexians. And so, ludo-narratively, Omen Hawker has foretold a strange, indecipherable reality, and then, his body bursting with the lightning crackle of Phyrexian death, he himself becomes the fuel for the invasion.

In Omen Hawker, the parergon and ergon of Magic, its framing device and framed tihng, seem perfectly aligned, the story and visuals and gameplay playing off one another to produce an experience that wouldn’t have been accessible otherwise. When you play it, you feel the narrative he represents.

Right?

There are other ways that MOM’s cinematic storytelling has a more ambiguous relation with narrative and framing. Magic’s conceits as a game don’t always correspond precisely to its narrative function. Story spotlight cards represent some of the most interesting examples:

If we’re operating under the assumption that Magic’s story succeeds when its parergon and ergon unite, these cards offer a tricky counterpoint. Although these cards represent story moments, it’s more likely to play them “out of order” than “in order,” at least from a narrative perspective. You can cast Elspeth’s Smite, which represents a key moment in MOM’s climax, or Negate, which represents Ajani’s decompleation during the denoument, on turn 2. You can only play Breach the Multiverse, the opening salvo of the invasion, around turn 7. You can play Seed of Hope, the story’s very last moment, on the very first turn. And not just that—you can play each muliple times in non-singleton formats, de-compleating Ajani or breaching the multiverse or replanting Wrenn over and over and over, turn after turn.

Certainly, there are some cards, like Corrupted Conviction, Into the Fire, and Storm the Seedcore, that work like Omen Hawker, both ramping up the narrative tension and propelling the trajectory of a game. Same for Transcendent Message and Invasion of New Phyrexia: while they can be played early in the game (contra their climactic timing in the story), they work best as last-minute, Hail Mary, here-comes-the-cavalry plays, just as Teferi’s invasion force itself did. But they, too, contravene story in the same way as Seed of Hope—being able to play them over and over, even after “future” story beats resolve, seems to disrupt the play experience.

Except, maybe not.

Let’s return to Omen Hawker. I argued above that the card’s brilliance is that, by combining eerie flavor text and art with a strange mechanic that could support the Phyrexian theme the turn after it was played, Omen Hawker represented the perfect unity of ergon and parergon.

But that isn’t the universal experience of Omen Hawker, is it? As I wrote in my last article, Magic is multiplicitous, and there are countless ways to experience any one card. Perhaps your first reaction to seeing Omen Hawker is the haunting thrill of uncovering the invasion, but you’re on the other end of the board—it’s your Omen Hawker, and you’re excited because your opponent has no idea what’s coming. Or perhaps this isn’t your first time seeing the card at all. Maybe your reaction was informed by past experience: a groan (ugh, they’re playing an Incubate deck), a smile (man, MOM was a fun limited environment), an eye-twitch (hopefully this’ll give me enough mana to get my Commander onto the battlefield). The card’s narrative power is one thing, but the parergon that frames it—the barrier mediating the world in which Omen Hawker means something and the world in which it’s a mere piece of cardboard—is made up of a rippling matrix of possible experiences, and so its meaning cannot be entirely fixed.

Such is true of the story spotlight cards, as well. When you play Negate, are you literally making Ajanis’s decompleation happen? In most decks, in most games, in most players’ experiences, no. That multiplicity should point us, I think, to a different understanding of the relationship between Magic’s ergon and parergon. It isn’t the case that there’s a clear, stable kind of narrative meaning-making here; the story might exist in one form as a sequential flow of events (namely in the web fiction), but in the game, it comes through more evocatively.

In a narrative-driven video game, a player makes a story progress through play; the right combination of actions triggers the extension of story. Magic doesn’t work like that. We aren’t initiating cutscenes through game actions. If anything, the reverse is happening: we’re using shards of story, fragmentary moments of Magic (Ajani’s curing, a knight-hero appearing on the horizon, a horrific omen) to initiate game effects (a counteractive response, a marshalling of resources, a preparatory move). In playing, we aren’t so much narrating these events or enlivening story fragments as sequential processes; we’re engaging in something like the mythic, touching some essence of what’s happening in a represented event.

And so it turns out that Magic’s parergon and ergon aren’t really so easy to distinguish from one another. In one sense, story is the parergon to justify game actions; the story serves a boundary between the outside world and the inside world, demarcating actions like drawing a card, turning a creature sideways, and rolling dice as meaningful for something. But in another sense, gameplay is the parergon that distinguishes story; game actions are the pretext for moments of story to emerge. The dialectic is constant, story framing gameplay and gameplay framing story, on and on—and in the middle of it is the experience we have that something is happening here.

So next time you’re playing Omen Hawker, think: is the card making the story happen, or is story making the card happen?

I immensely appreciate all the support I’ve received on this Substack! If you have a thought, disputation, or question that interests you, share it below. My next article will either be a deep-dive into myth and legends or more thoughts on March of the Machine—namely battles. Leave a comment if you have any ideas!

What a great piece! I love the description of how playing a game used to represent two planeswalkers battling with spells and now, it represents more of a cinematic event. Very insightful!