One of the funny little quirks of Magic’s Commander format is that it cleaves between intense individuality and intense genericity. On one hand, Commander is the format where you can play crazy cards that are too slow for Standard or Modern, where you can go to extreme lengths to customize your favorite deck, where you can make a play—and win—in a way nobody’s ever seen. On the other hand, Commander can sometimes run the risk of making individual cards feel generic—the way every Blue-Green commander (seems) to do the exact same thing, the way that running a theme in a large deck necessitates using a ton of repetitive cards (the way a GW token deck, for example, might seem every variation of Soul Warden or Doubling Season), the way that EDHREC can make so many decks feel like they’re using the same staple cards.

There is no more perfect case than Sol Ring.

Sol Ring is the pinnacle of uniqueness. It’s fully legal only in Commander and its child formats (restricted in Legacy) and it’s a distinctively powerful mana rock (a mana rock being an artifact that can produce mana). Sol Ring is the pinnacle of genericness: it’s such a staple that every single deck runs it.

The same is true, though to a notable lesser extent, with other mana rocks. If you need some mana fixing, there’s always a case to be made for Commander’s Sphere. If you’re running a multicolor deck, toss in a guild Signet, a wedge Banner, or a Shard obelisk.

Of course, it’s not that simple, is it?

Mana rocks are generic. Mana rocks are also infinitely diverse. This is true, first of all, from a gameplay perspective.

For example: Turn 1. You play a basic land, then tap that land to play Sol Ring, then use the 2 mana from Sol Ring to play an Arcane Signet. If you have another land in hand, then by turn 2 you’ll be able to bring out almost any of the over 1500 converted-mana-cost-5 commanders in Magic.

This is assuming that your opening gambit is to play your commander. Not to worry: there are almost 5000 cards that cost 2 colorless mana and are CMC-3 or less.

Perhaps you know your opponents love removal spells, so you want to be conservative. That’s okay. In another situation, you might go basic land→Sol Ring→Swiftfoot Boots, ensuring that your creatures will be protected.

Not to mention, of course, that deceptive yes/no question in which is contained a bundle of countless decisions: the mulligan. Is it greedy to keep the Sol Ring with only one land in hand? Is it a waste to keep it when I have four lands in hand? Will it contribute to my strategy?

Sure, if we view a Commander game from the outside, it’s easy to say that decks are broadly similar. But if we look from the inside, from the actual experience of playing, we see that what looks generic actually opens up a panoply of possibilities. What makes Sol Ring and its fellow rocks great isn’t just what they are, it’s what they can do.

The real reason I love mana rocks goes hand-in-hand with the diversity of play. They provide some of the purest flavor in Magic; they don’t just give you a suite of options for playing, but also help channel the ideals behind the game.

The idea of mana rocks’ storytelling power really hit me during a prerelease event for Modern Horizons III, when I was looking over the flavor text for the Medallion cycle.

Before MH3, the Medallions had no flavor text—just a single line of rules text appending tightly framed images of each artifact. The minimalism was effective; it lends gravitas to the Medallions, as though the player has just uncovered an ancient and indecipherable relic from an alien burial ground. But the new flavor text is effective, too:

It is a sun-dappled glade in the morning, the aroma of spring’s first blossoms, and the melody of birds chirping in a joyful chorus. It is life.

It is a helping hand reaching out to the downtrodden, the acrid-sweet tang of burning incense during prayer, and the harmony of voices uplifted in unison. It is faith.

It is the imposing heft of a ruler’s scepter, the stench of death after a victory in battle, and the mournful wail of an enemy kneeling in supplication. It is power.

And so on.

Magic, as I’ve discussed before, channels a kind of philosophical idealism; it’s not just that things have power, but also the concepts associated with things. The game plats on the way that ideas—whether fictionally or in reality—can meaning into the world before us. Each color represents a set of ideals, as the Medallions indicate; each of the twenty two-color and three-color combinations folds these traits together (often in in different ways—the Naya shard, Ixalan’s Sun Empire, and New Capenna’s Cabaretti are all color-coded as Red-Green-White, but each has a distinct way of embodying a way that freedom, unity, and harmony might blend together).

These idealities structure the way that story emerges in the experience of Magic. Playing Black and White embodies an attitude and set of flavor coordinates as much as a set of strategies; certainly, a White-Black deck will mean aristocrats or lifegain or sacrifice strategies, but it will also appear in imagery of vampires or zombies or ghosts or bats or banker-priests, and it will embody a playstyle of ruthless accumulation and byzantine machination.

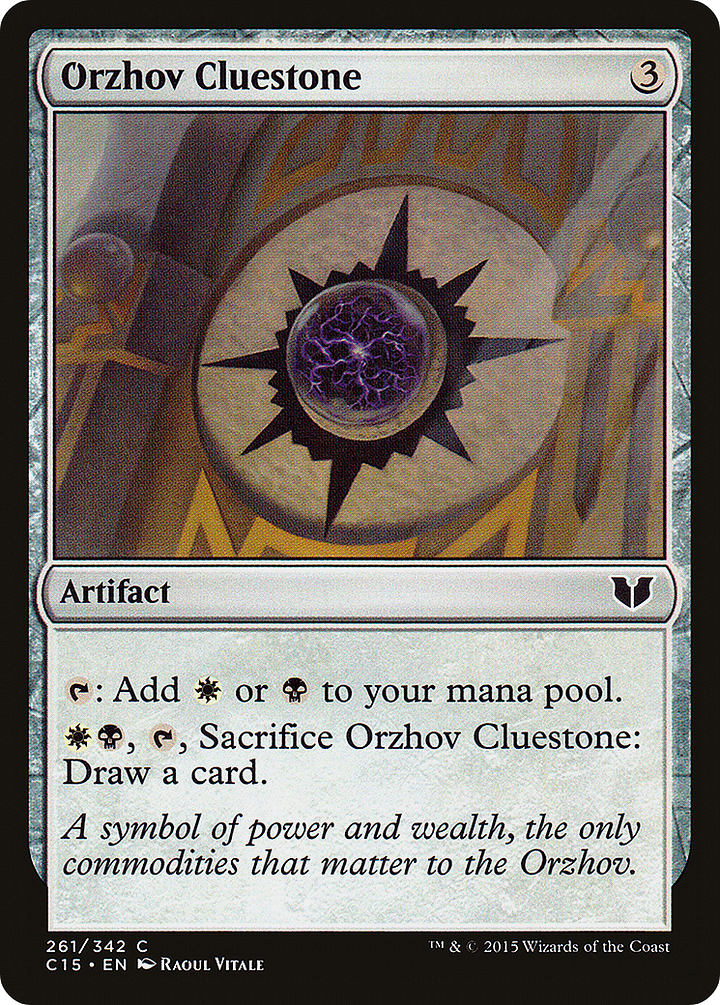

Mana rocks are foundational to this kind of ludic-storytelling blend. Precisely because they function so simply and so independenlty of any one deck’s theme, they embody the essence of what mana—resources, power, action—mean to that deck. Take the BW rocks:

The Orzhov Cluestone: A symbol of power and wealth, the only commodities that matter to the Orzhov. As this deck performs, strength means hoarding and protecting power through hierarchy.

The BW mana rocks are contraposed against dark, extravagant backgrounds, the artifacts seeming to radiate numinous power. They’re encircled by dense knotted lines or towering cityscapes hallways leading to nowhere, materializing power as a dense architecture with a clear order. Strength, to them, is hierarchal and byzantine; like a successful BW play, it’s convoluted, but there’s always someone pulling the strings.

Mana rocks, if we pay attention to them, reframe gameplay such that the player isn’t merely grabbing random cards to fulfill a win-condition. Their play is animated by a principle, with power and energy all its own. The Orzhov rocks, for instance, aren’t arbitrary images; they symbolize that Hierarchy itself is appearing, coming into being, providing power, to the player.

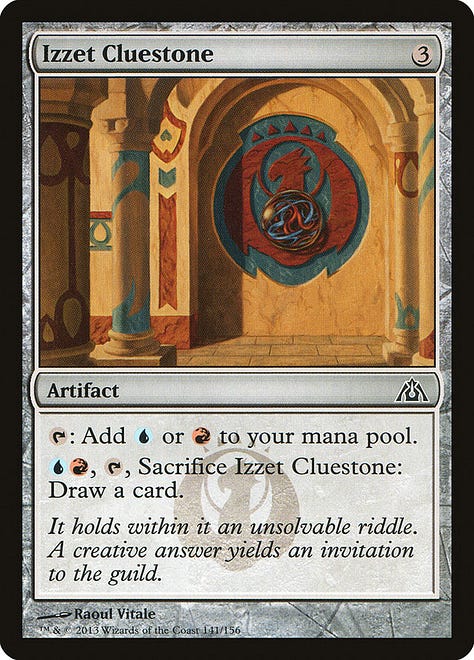

Such is true, of course, for the other mana rocks. When you play Green-White, the narrative goes, you’re drawing power from the ideals of unity and solidarity; Red-Blue, passion and ingenuity; Black-Green-Blue, domination and decadence. In their flavor and art—in the sun-dappled glow of diverse plants amidst a solid stone background, of whirring machinery glowing electric blue, of a single bowl of opulent fruit set against imposing palace walls—they call forth the ideals to which the colors correspond. In using a mana rock, a flavor defines what it is that their deck means, in the scheme of Magic.

It’s also true of the colorless mana rocks, which outnumber the colored mana rocks by quite a lot. Although there are an immense array of them, from Ashnod’s Altar to Worn Powerstone, each one channels an idea of what mana—the vital fuel of play, the energy of life—really is. Do you thrive by uniting disparate powers under one cause, as in Throne of Eldraine? Does acquiring power mean constructing massive machines that spurt out deracinated energy, like Thran Dynamo? Unfurling the fragile and fractalized webs of consciousness, like Thought Vessel? Burning away excess or supplicating yourself before capricious powers or sapping life from other things?

Does the elan vital come, perhaps, in the haunting form of Phyrexian Altar, in which power is attained by bowing before an all-consuming unknown, a force that will give you anything you want—so long as it fits on the stone maw of this abyssal hunger? Each rock is utilitarian, yes, but it also represents what idealized meaning represents the source of your abilities.

A player has boundless opportunity for meaning-making even within a single artifact—as in the case of Arcane Signet, which has eighteen distinct artworks (so far, anyway—Donny Caltrider took a great survey of the Signet’s art visual history last year). The signet, as its name implies, emblemizes—bodies forth power itself. In tapping into the tiny object, a user gains a burst of pure power from beyond themselves—in gameplay terms a perennially valuable one mana of any color in your commander’s color identity.

I initially wrote more about these artworks, but I had so much to say that it made this article go way overboard. I’ll satisfy my own sick urges by remarking that nearly all the (non-Universes Beyond) Arcane Signet arts and flavor texts point to something mysterious or unexpected. The strange enchantment of Dan Scott’s; the mute antiquarian mystery of Dan Frazier’s; the whimsical wonder of Dani Prendergast’s first Signet and the haunting, esoteric mysticism of her second; the sidereal power that flows from Rovinia Cai’s Tarot-inspired Signet; and, the prismatic energy flowing from my favorite Signet of all (partially because it’s incredibly to look at and partially because a friend gave it to me), Gaboleps’ Infinity Gauntlet-style Signet, which which seems to call into itself the very forces of Creation.

If all artifacts visualize and enact a sense of where power comes from, the Signet seems to point to a most eminently transcendental source: by tapping into the Arcane Signet, you call on a power beyond yourself and mold it to yourself. It’s a mystical kind of power, the power that—in keeping with Arcane Signet’s crucial function in the Commander format—allows you to pull off incredible feats by remixing the forces of creation (or maybe just remixing the extensive catalogue of Magic cards) for yourown needs.

The Signet, like every other mana rock, visualizes and thematizes where, in Magic, power comes from: idealities. Whether it’s the human ideals of the color combinations or the paths-to-power in colorless artifacts or the pure Mystery of the Arcane Signet, these artifacts disclose that, in the cosmology of both Magic’s universe and its gameplay, the things we swear to aren’t just abstractions: they sustain and enliven us.