Messianic Time in Edge of Eternities

On the future of the future

Before I begin this piece of Edge of Eternities, I’d like to direct you to a different piece of Edge of Eternities writing that I published recently: “Edge of Eternities and the Power of Difficulty” on Hipsters of the Coast. The article takes a look at Seth Dickinson’s astonishingly good and sometimes challenging Edge of Eternities web fiction, and makes the case that, in fact, difficult writing is a great tool for building a fantasy world. It was a real delight to work with everyone at Hipsters, and I hope you give the article a read!

In the meantime, there’s so much more to say about EOE.

Although the set’s prerelease hasn’t begun at the time of writing, I’ve nonetheless been utterly entranced during the month of July. The art: amazing! The mechanics: cool, I think! The aforementioned story: gobsmacking. The worldbuilding: monumentally great. If Tarkir: Dragonstorm both returned to and revitalized the roots of Magic worldbuilding, Edge of Eternities has helped it grow in amazing new directions.

There’s so much to say about the set that it’s impossible to countenance in one article. So instead, I’ll be focusing on one twofold theme that offers a key into the brilliance of the set: the nature of time and the presence of religion.

Prelude: The Future

A structuring motif in Edge of Eternities (in the web fiction, the worldbuilding in the art, in the mechanics) is time itself. This is fitting, I think, for two reasons.

First, getting immersed in a sci-fi space opera world (especially one with hard science fiction aesthetics) means grappling with time as a cosmological reality—with the relativity of space and time, cosmic entropy, travel over impossibly long distances, and so on. Sci-fi, at once rooting itself in our universe and expanding beyond it, invites us to grapple with the kinds of strange metaphysical questions already immanent to our world, the odd indecipherables that undergird existence itself.

Second, and more importantly, space opera worlds necessarily draw on our cultural relationship to time, insofar as they’re about the things that seem to belong to the future. Space-themed classics variously draw on or ironize this implicit future-oriented gaze: Buck Rogers awakens from a 500-year coma; Star Trek inhabits a world claiming to be the future of our own; Star Wars plainly evokes the future but also labels itself upfront as taking place “A long time ago.”

The brilliance of Edge of Eternities is to adapt this subtext and integrate it into the text itself. From the player’s perspective, we enter into a world that might look like the far future of a plane like Dominaria—but the characters, factions, and cards grapple over and over with the question of time itself.

Mechanically, time shows its face most explicitly in Warp, a mechanic appearing on 50 cards in Edge of Eternities, in which a card momentarily disappears and promises to reappear later. Lander tokens function in a similar way, setting up the appearance of a land in a turn or two.

Things get even more explicit, though, in the set’s worldbuilding and story. The Kav, having destroyed their homeworld, now find themselves spread across three worlds, two real and one prospective: Kavaron Before, Kavaron That Is, Kavaron Tomorrow. The Drix seem to organize their existence around the horror of the Fomori-Eldrazi War, and focus all their efforts on preventing any future apocalypses—notably, in Aimee Ogden’s “The Wefthunter,” by dealing with time travel devices. The Eumidians maintain a philosophy of explosive-but-unifying growth, hurtling asymptotically toward a future in which their bodies and the world they’re terramorphing become congruent. And of course, Dickinson’s web fiction is entirely organized around an artifact that alters past events.

But the most fascinating of all, to me, is the way that the set’s approach to temporality and futurity bears out in its clashing religious factions, the Monoists and the Summists. I touch on them briefly in my Hipsters article—to quote myself, “The Monoists worship gravitational force, inner truth, the unknowable void of the self, the possibility of another world; the Summists revere cosmic light, the mathematical sublime, scales of time and meaning beyond mortal comprehension but bounded by finite existence.” But there’s so much more to say.

Number Our Days

The Monoist and Summist faiths are both built around an essential recognition of temporal boundedness—of the universe’s inevitable heat-death.

For the Summists, the response to inevitable decay is to stretch out the universe as long as possible. They seek to propagate light (literally, by fostering suns) in order to mathematically maximize the amount of life that can exist before everything goes dark. For the Monoists, the secret to life is to steer into the skid. Embrace entropy, recognize that this mortal world is just a prelude to the “Next Eternity,” the presaged reality on the other side of supermassive black holes.

It’s a deliciously elegant theological debate, I think, to rivet to a game like Magic. A single game of Magic has only one outcome—someone wins—but the path to reach it and the meaning of the journey are entirely up to the player.

This focus on time allows the Summists and Monoists to defy the cliches propagated in both non-Magic fantasy/sci-fi and past Magic sets alike. They are not, respectively, Space Christians™️ and Space Satanists™️. If anything, both faiths seem inspired by medieval and early modern Abrahamic faiths.

The Summists, with their techno-chivalric aesthetics and theocratic governance, evoke Counter-Reformation Catholicism, while their theological emphasis on determinism and their fixation on precise mathematical calculation brushes against eighteenth-century Deism and nineteenth-century Utilitarianism. The former is deeply ceremonial and focused on transcendent values like life, and the latter emphasizes the essential mechanical dependability of the universe. For Deists, God is like a great clockmaker who set the natural world ticking, and for Utilitarianists, the most ethical course of action is to calculate how to work this clock to maximize good.

Such faiths, which refract through fiction into Summism are all grounded in a devotion to life itself. But unlike messianic faiths like Catholicism, the Summists grimly accept the finality of universal decay—and with this recognition in mind, they establish a devotion to the whole expressed through grand calculation. Their devotion is to life in the aggregate, not individual will or localized morality. The flavor text on “Luxknight Breacher” suggests as much: “Only when a vessel is emptied of shallow ego may the depths of light flow in to fill it.”

You’ll notice that in card art, Summists are rarely depicted alone:

Even if a singular figure is the focal point of an illustration, they’re typically flanked by their comrades—and are often cloaked behind blank golden faceplates. It’s fitting, for this reason, that White actually has a narrow plurality of cards with the Warp ability in EOE. Warp encourages you to distribute your resources strategically, tossing an individual into the fray and figuring out the best time to bring them back from exile.

Elsewhere, artistic composition plays a role in evoking Summist theology:

In Forrest Imel’s astounding illustration “Honored Knight-Captain,” collectivism is both literal and figural. We might read the titular captain as training the other warrior at the bottom right of the painting—or we might interpret them as belonging to different times, the discolored other warrior being either a shade of the future or an echo of the past.

Either way, Imel’s imagery forges a metaphysical link between them. The elegant gold-leaf geometric design hovering behind the Knight-Captain at once represents his cape and visually interlinks him with the other warrior. The Sum, here, is visualized in the imagistic language of Christian icons: any individual is cosmmically bound to a whole that far exceeds them, across space and time.

And as EOE’s web fiction makes explicit, Summist theology makes its conception of time foundational to its existence. One of the most dazzling moments in Dickinson’s web fiction comes when, in an attempt to contain the reality-altering Maguffin at the heart of the story, Haliya uses highly mathematical Summist doctrine to fix herself in time—adapting her biometric information into frequencies for transmitting prayers, sending messages coded to a pendulum moving with her, and more. For the Summists, this is where the secret of reality is to be found: in the dependable mechanistic logic governing the universe.

But time also inflects Summist morality. Haliya, dimheartedly parroting Summist talking points in a later episode of Dickinson’s story, stammers that “the urgency of visible suffering and the limits of human scale sensitivity” actually muddle “the long-term clarity of the Sum.” Of course, things are more complex, too: Haliya’s sense by the end of the story is that the Sum must be calculated incorrectly if it demands the death of thousands of innocents.

The suggestion here is of deep time, calculated long-term contingency over immediate action. The Summists know the unvierse will end—and they’re going to make sure everything goes exactly according to plan.

Ex Nihilo, Ad Nihilo

The Monoists are, too, governed by religious hierarchy—but are distinguished by their opposite view of time and decay.

Although it might be easy to pigeonhole them as “space bad guys,” the Monoists are, as James Pearce (MTGCritical) has recently suggested, are an essentially ontological faction.

Their dark arcane aesthetics, their exaltation of free will above all else, and their fascination with the transcendent mystery of being and non-being evokes a whole host of less menacing assocaitions: the mysticism of Saints Augustine and John of the Cross, the theology of Martin Luther and Søren Kierkegaard, and life-unto-death drive of some twentieth-century existentialists. In these strains of thought, the self is not extraneous to existence but rather essential to it: it is the mystic gravitational center of being itself, the very mystery that holds all other mysteries.

The Monoists, in tune with such thinkers, locate the relationship between present and future, life and decay, in the individual person. Unlike the Summists, they have a singular Messiah: the Faller, a mysterious figure who seems to be perpetually plunging into all Supervoids and who transmits messages from the Next Eternity.

Their belief is gathered on gathering and singing this prophet’s song, as in the “Antiphon” from the gospelic text “The Theorem Unending and Final” quoted on “Gravkill” (an “Antiphon,” by the way, refers to the refrain to chanted Psalms in Orthodox and Catholic religious services—hinting, again, at the influences of the esoteric on the Monoists):

“‘‘Sing! When the Faller reaches the end of his journey, all things will arrive at the Zero Point.’”

Such individualism, importantly, is not a kind of heartless cartoony evil. Indeed, as Dickinson’s Alpharael observes early on in the EOE story, “One of the tenets of Monoism is absolute respect for individual will,” and “in a society of total emancipation and enlightened selfishness, there is still empathy, because most people, Alpharael thinks, have an intrinsic need to connect.”

There’s a funny paradox, here: if they care so much about the individual, why do they seek to accelerate cosmic decay? The answer, in fact, is quite the same for the Monoists and the Christian mystics I mention above: the will is absolute not because we are rational agents seeking our self-preservation, but rather because it’s the profound mystery through which the unknowable is dimly accessible to us.

For this reason, worship of the Zero Point is nothing less than the worship of the individual soul. It’s put perhaps most beautifully in a line from Rich Larson’s “Compact Me to Zero”:

As the Faller seeks the dark peace of the Well, I seek the dark peace within me. As light bends away from the Core of All Things, let my thoughts bend away from my being. As the supervoid stills the Chaos Universal, compact me to zero and let me be still.

For an equally poetic rendering of this truth, look no further than the two poems written by Raphella, Alpharael’s sister, inscribed in the web fiction:

•

All

All creation

All creation in a

All creation in a point

the point of all

creation in

all in

all •

I

will

never recur

in all the zettaquettaquettameters

of space and all the aeons

of time(Incidentally, I think that there was a flavor snafu: the Edge of Eternities: Commander’s “Sol Ring” refers to this poem as a “Sunstar loop-mantra,” and though the web fiction is not composed by the same people as flavor text, but the sentiment is clearly more Monoist.)

All of the universe’s mystery exists, the poem’s attest, in the singular condensed point of reality, the utterly invaluable individual.

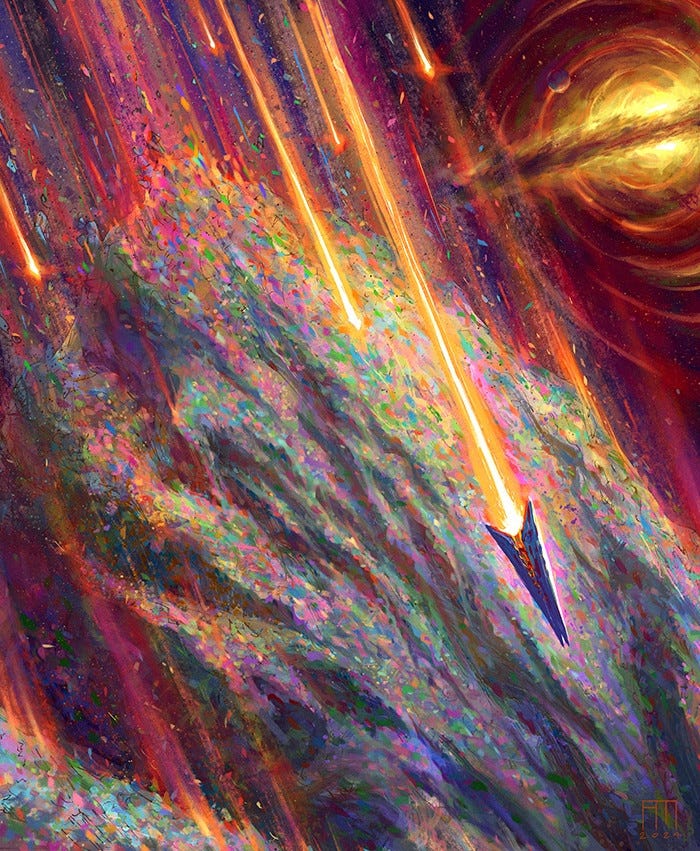

The mysticism of individuality reflects, too, in EOE’s Monoist cards. Their art and flavor text tends to be a bit sinister—a real shame, in a way. But there’s still a mystical nobility in them, one rooted in individuality. In almost every card depicting a Monoist, their faces are bare and expressive, as are their bodies:

In Alix Branwyn’s stunning “Chorale of the Void,” the individual is made the vocal point of a luminous teal-and-purple plasmic swirl, behind which hovers the supervoid itself; their robes flow in elegant arcs, seeming to plunge directly into the void—visually freezing the process by which they, themselves, are sucked past the event horizon. Viko Menzes’ hilarious and haunting “Lightless Evangel” does the same, stretching its constituent lines such that all reality (and the Evangel’s victim) are sucked into the black hole at its literal center.

There’s beauty to entropy, for entropy implies individuality, and in the individual is a path to transcendence.

Space and Time

These long detours bear out what, to me, is the beauty of setting a space opera set against a religious war—and, no less, a war based on time.

For one thing, a space opera religious war troubles our own conceptions of pastness and futurity: while some might be inclined to relegate religious mysticism to the past, to see it as an artifact of the medieval and fantastical, EOE asks what it might look like for faith to persist into a future just-barely imaginable.

Even more, its faiths grapple with the very problem of time itself: finitude and eternity, singularity and expansion, messianism and Deism. And, perhaps most importantly of all, they locate the place of the individual within such unimaginable schemes of time. They ask whether the ego is the path to transcendence or the path away from it. They ask whether past and future are morally charged, and whether the worth of one person means anything in the longue durée of the universe.

I invite you to keep those questions in your back pocket when you choose your draft archetype. It might eat into your time. But that’s going to happen anyway, isn’t it?

Reading this and your thoughts on the Summists really makes me think of the first few Asimov Foundation books. Using math and grand calculus to "predict" the future and align actions with the results of the equations. It's a cool concept. Have you read Foundation? How do you compare the differences between math that leads to a desired future (most good, Asmiov) vs math that acknowledges the end of the universe, but tries to avoid the worst situations (least bad, Summist)? I suppose the difference is subtle, but interesting nonetheless.