One of the core narrative features of science fiction and fantasy is the Big Battle. In the chronotope of a fantasy world—which, as I’ve discussed before, is the particular configuration of space and time that shapes what counts as an “event” in a given story—the Big Battle is the focal point. All events lead to the moment when the big battle occurs; the details of its topography are more essential to the story than most other spaces; more chapters are dedicated and greater detail is enumerated to this space than anything previous. And then, once the battle ends, the book isn’t far behind. Perhaps the sharpest example in contemporary science fiction/fantasy is the “Sanderlanche” of Brandon Sanderson’s fiction, in which a considerable fraction of the given book is dedicated to the explosive climax; where the early part of the book focalized singular spaces and covered whole days in one chapter, in the Big Battle multiple spaces become directly interlinked and time compresses such that one chapter can cover mere minutes.

Magic is no exception to the “Big Battle” chronotope. Although there are many models for arranging time and space—like, as I’ve discussed in my article on Bloomburrow, the time-space of the Road—the momentous clash is a major one. The Big Battle is built into the game’s mechanics, after all: every happening in a game of Magic consists in a confrontation between forces, framed in the game’s initial in-universe fiction as battle between planeswalkers. Indeed, in the game’s most popular format, play is a confrontation between armies, each led by a titular Commander.

So too for worldbuilding, particularly the tentpole sets that are cinematically inspired: the Eldrazi incursion of Battle for Zendikar, the Phyrexian Invasions of Apocalypse and March of the Machine, and the titular War of the Spark. In March of the Machine, the final-fight chronotope was enshrined in cardboard with the introduction of the Battle-type card; in the same way that language in a novel creates the spatial constriction and temporal distension a final battle, Battles make March of the Machine’s epic engagements the fulcrum of multi-turn board states.

To be sure, and befitting of their climactic status, these sets are not the rule. Sets like Throne of Eldraine sketch out a world, with a broad story serving as backdrop but not dominating the entire set; even those that revolve around specific conflicts, like Dominaria United, are structurally loose, roving around the plane over a wider span of time.

But 2025’s sets—revisiting Tarkir and Avishkar—have, I’ve noticed, done something different. Their concern is less with climactic catastrophe or epic, decisive battles. They are concerned with something else: what it means to rebuild after the dust settles.

Avishkar: After the Revolution

Avishkar’s rebuilding was what germinated this article: the first inklings of rebuilding, as a theme, came to me as I read the Aetherdrift world guide, which I’ve written on previously. In this document, Miguel Lopez (who, besides the Aetherdrift guide, has written some of the game’s best world guides and short stories) gives us the first taste of Avishkar: “The Consulate that led Kaladesh has also been done away with following a popular, nearly bloodless revolution.”

Further in the guide, we learn more: Avishkar “is a plane ascendant, its people united behind the banner of a popular revolution made real,” and it’s governed by a democratically elected body The new planar government, the Avishkar Assembly, is a democratically elected body of representatives from the plane's eleven administrative districts.

The details of this popular movement, called the Indigo Revolution, are a little convoluted, but they emerge out of an interesting twist: a failed revolution. The titular movement of Aether Revolt, which centered on a movement against the authoritarian Consulate, stagnated into disappointing reformism—and in the aftermath of March of the Machine’s Phyrexian Invasion, this centrist government was toppled. “City and district-level mutual groups, criminal organizations, and more radical revolutionaries stepped into the vacuum, managing the chaos and fighting back against the Phyrexians. When the invasion ended, the victors would not accept a return to the norm.” From this alliance emerged the Indigo Revolution, “orchestrated by radical members of the reformed Consulate, partisan revolutionaries across Ghirapur organized under the New Culture Collective, along with various other labor, peasant, and student groups” and founded on abolishing the plane’s “artificial scarcity,” in which “[p]eople who were poor were engineered to be poor by the economic system that dominated pre-invasion Avishkar.”

What’s striking here is that the worldbuilding team’s vision and Lopez’s language are evoking a different kind of revolution than Magic had seen before—not the dramatic, violent, conventionally heroic upheavals of Aether Revolt, but the more utopianist, populist thought of real-world political activism. This revolution is more Dean Spade than Robespierre.

Aetherdrift’s art direction channels a similar spirit of populist renewal. The land cards of Kaladesh were impersonal and imposing, absent of humans and harshly contrasting the natural and built environments; those of Aetherdrift bring ecology and architecture into lavish synthesis, fill the cityscape of Ghirapur with lush color, and bring individual figures into the foreground.

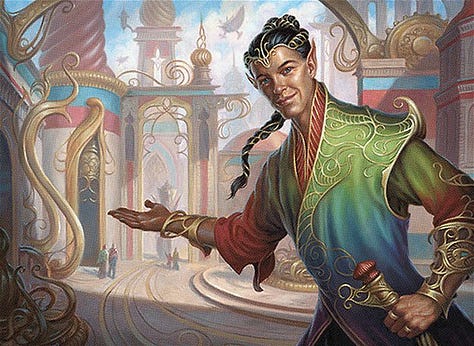

In a similar way, the art for the creatures of Kaladesh tended to shroud individuals in darkness, make them mere passers-through their environment, or emphasize the lavishness of their social class; those of Aetherdrift are more brightly lit, are posed with more dynamic involvement in their environment, and interpolate gritty aesthetics with fine filigree. Scott M. Fischer's art for the new Gonti, Julia Metzger's art for the new Oviya Pashiri, and Carly Milligan’s exceptional “Elvish Refueler,” are great examples. This is a world in which the very character of aesthetics has changed, in which people are actively involved in their world across the boundaries of class.

In this sense, Avishkar’s design accords with a burbling chorus in the audiences of science fiction/fantasy fiction. Contemporary writing and criticism, from the work of science fiction writers like N.K. Jemisin to that of canonized authors like Octavia Butler and scholars like the late Frederic Jameson, have attuned S/F’s possibilities not just for entertaining us but for helping us envision other worlds. In these approaches, science fiction/fantasy (or, as it’s sometimes rebranded for palatability, speculative fiction) contends, as we all do, with the torrent of political calamity that is the present moment—by asking what else might be.

To represent this social transformation, Aetherdrift decidedly does not engage with the chronotope of the Big Battle, the culminating event in which time thickens and the works’ constricts to one place. It still revolves around a single dramatic event (the set is about an interplanar death race, after all), but the race’s distended timespan and spatial reach means Avishkar is not the site of an apocalyptic battle; it’s a backdrop.

But backdrop doesn’t mean incidental. On the contrary, because The Fate of the World wasn’t at stake, Avishkar itself has room to breathe: it is allowed, more simply, to be, to serve as the fleshed-out but still-evolving world through which the race traveled. As a result, we can grasp what it feels like for this world to rebuild.

Tarkir: After the Past

Even more timely than the reborn Avishkar is the brave new Tarkir of Tarkir: Dragonstorm. I’ve been compsoing this article as previews dropped, and I’m certain I’ll dedicate another article to the set, but for now I want to touch think throught the way the world is rebuilding.

The worldbuilding team for Dragonstorm has had, I would wager, as lofty a task as in Aetherdrift. We haven’t been to Tarkir in ten years (as opposed to the eight we’ve been away from Avishkar), which means that returning to the plane would be freighted with a literal decade of anticipation. What’s more, while the Aetherdrift team had to tackle the largely bungled representation of South Asian culture in Kaladesh, Tarkir was even more complicated: they had to address certain problematic cultural features, but they also had to synthesize everything players loved about the clans and had to do so in a way that jibed with Tarkir’s already wonky continuity. A heavy burden, indeed.

Personally, I love what they’ve done with the new Tarkir. Besides debuting a bevy of astonishing card illustrations and wonderful web fiction, the worldbuilding for Tarkir has helped realize another dimension of a “rebuilding world”: what conflict looks like to build a society out of the past.

The Tarkir of Dragonstorm is like and unlike what we’ve seen previously. Where Khans of Tarkir shows a version of the plane dominated by the five clans and Dragons of Tarkir shows us a version that, after Sarkan Vol’s time-traveling adventures, was crushed underfoot by the revived dragons, Dragonstorm attempts to find the best of both. In this version of Tarkir, the remnants of the clans rebelled against the Dragonlords, recovered many of the traditions of their ancient cultures, and established themselves as rulers of the plane—alongside the spirit dragons. (Now, by in-universe chronology, Tarkir has changed pretty dramatically in the few years since Dragons of Tarkir takes place. But that’s what suspension of disbelief is for (it seems to me more fitting to find a ten-year-old plane radically changed than to find it the same as when we left)).

Like the Indigo Revolution of Avishkar, this seismic social change is the pretext, not the text, of Tarkir: Dragonstorm; we arrive in the world after the rebellion against the dragons. But that doesn’t mean we miss its transformation: on the contrary, the set inhabits us precisely in what transformation itself feels like.

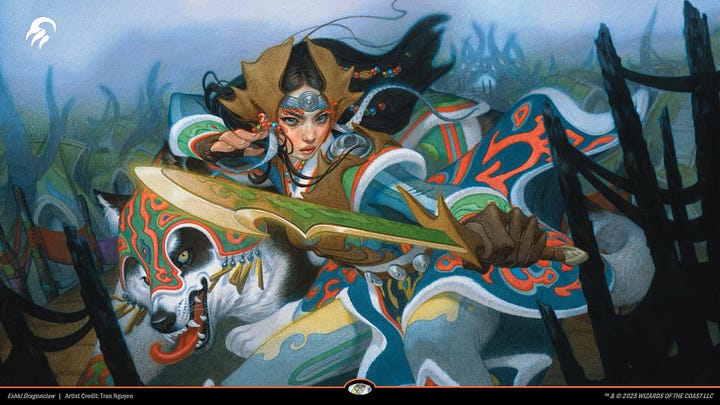

There are, most obviously, aesthetic changes. Where the original Abzan tended to be bedecked in muddy-brown armor dominated by diagonal points (invoking the scales of the then-extinct dragons), the new Abzan wear robes and armor of purple, green, and gold, evoking a fantastical version of the Ottoman aesthetic that inspired the clan’s original design—and visualizing their white/black/green color pie alignment. Triangular points and curves still appear, but now a central motif is crackling golden energy—the very essence of their ancestors, which is infused into the gaping jaws in their chestpieces. The Temur, similarly, now wear bright crimson, blue, and green outfits etched with complex geometric patterns, drawing more explicit inspiration from the Sakha of Siberia; these designs, like those of the Abzan, also express the Temur’s Red/Blue/Green color alignment.

Both these styles are profoundly different from those of the original Tarkir, and not in a bad way. Metatextually, they speak to the trends of contemporary Magic art, which leans more on popping color rather than the neutral tones that dominated the early-to-mid 2010s. Indeed, it was actually around the time of the original Tarkir sets that the seeds of this transformation were planted: 2013-2015, the years during which Tarkir Block was being designed and released, saw the first appearances by Mark Winters, Zack Stella, Jason Rainville, Magali Villeneuve, Chris Rallis, Josu Hernaiz, and Victor Adame Minguez. While these artists only occupied minor roles at that point, in the following years their work (as artists and art directors alike) would install vibrant colors and popping luminosity as central to Magic’s aesthetic. In a beautiful sort of way, then, the new Tarkir both makes an aesthetic break and shares a deep continuity with the original.

Setting aside trends in Magic’s visual history, the redesigns look great on their own. They’re memorable, striking, and cool. Even more, they’re visually distinguishable from one another (something of a problem in the older Tarkir sets; the muddy colors and generic outfits of the original Temur, for example are especially hard to parse on a tabletop or screen), and paradoxically, this distinctiveness helps players imagine how the clans might interact with one another. Beautiful as the old Tarkir art is, it’s difficult to conjure a strong visual narrative for two factions meeting when they’re both dressed in white and muddy brown—but when they look discernibly different, the possibilities for visual storytelling explode. Such is evident in Tuan Duong Chu’s “Barrensteppe Siege, ” where the Abzan’s golden-green colors, verticality, and triangle-dominated lines strike a clear contrast with the blood red, electric purple, horizontal, and curve-dominated visuals of the Mardu. It’s a testament to these designs that even in the illustration’s overcast climate, we still get a sense of who the Abzan and the Mardu are (immense, stalwart, hierarchical, warm; diffuse, immense, dynamic, electric).

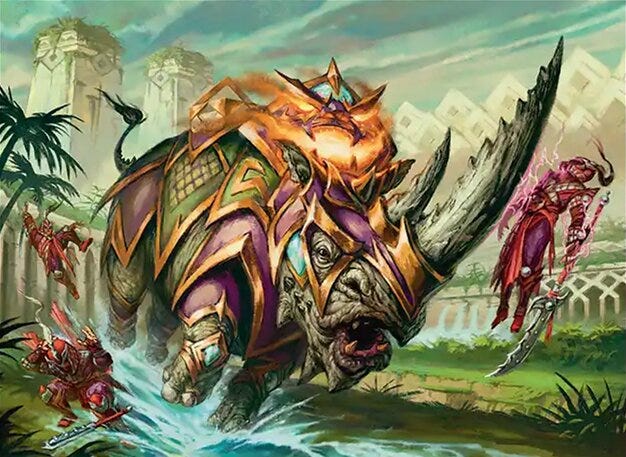

Yet, at the same time, what’s interesting about the new aesthetic is precisely that it’s in dialogue with the clans’ old aesthetics. Enfranchised players in particular might carry with them the awareness that this isn’t how it used to look, but the set’s design clearly invites such considerations (without spiraling into navel-gazing referentiality). Illustrations like Olivier Bernard’s “Smile at Death” and James Bousema’s “Skirmish Rhino,” for example, explicitly invoke the Tarkir of old but cast them in a radically new light, both registering our knowledge of what came before and forcing us to contend with how that old thing has transformed. Bousema’s new rhino roars into action, its sharp diagonal lines and popping colors registering an explosive vitality that plays with the muted colors and blocky density of Volkan Baga’s “Siege Rhino.” Similarly, Bernard plays with the composition of Anastasia Ovchinnikova’s much-beloved “Alesha, Who Smiles at Death”: Alesha’s pose is flipped, the sword in her right hand now raised in bold exhortation. Continuity, but transformation.

The same is true in the set’s absurdly expansive world guide and excellent web fiction. The former, written by Lauren Bond and DK Billins both implicitly and explicitly attends to Tarkir's transformative changes. We learn about how each clan revived—and revised—the traditions we saw in Khan of Tarkir, but we also go into extreme detail about their culture, their architecture, their art styles, their military, and their philosophy. The clan philosophies are especially intriguing because of how they actively and explicitly recast those of the old clans. The edicts of the Mardu, for example, have transformed: where the Mardu of Khans held fast to the brutal (and more than a little fascistic) Edicts of Ilagra (“To conquer is to eat. To rule is to bleed. Victory or death”) the new Mardu profess the Decree of Thunder: “Loyalty is earned. Community is strength. Victory is survival.” The parallelism of the old and new philosophies draws attention precisely to their differences, to the way that, for the Mardu, rebuilding from the past means not just redsicovery but reinvention. In the chronotope of rebuilding, that’s what we’re led to experience—not the apocalyptic battle but the moment of rediscovery.

The most striking changes appear in Dragonstorm’s stellar web fiction, which showcases one of the key principles in the set’s rebuilding world: dissonance. Each of the side stories shows off a different way that, amid the clans’ rebuilding there exists not monoculure but conflict, each faction experiencing internal conflict over their future. K. Arsenault Rivera’s “Together Survives the Pack” illustrates how the Temur must contend with whether being in harmony with the world means including all or letting the weak perish. Rhiannon Rasmussen’s “Siege Blossoms” shows an Abzan adoptee in a fractious conflcit between individual ambition, genealogical discrimination, and service to the collective. In Seanan McGuire’s “Where Lightning Tells Our Story,” a young Mardu warrior must choose between devoted compassion to clanmates or a brutal commitment to action. Michael Yichao’s “The Unknown Way” foregrounds how the Jeskai are divided between martial combat and scholarly learning. And, perhaps most explicitly of all, Marcus Terrell Smith’s “Betrayal” exhibits what it looks like when some want to return to the old: Smith’s protagonist is a Sultai traditionalist who spits in the face of the new egalitarian clan, and in his quest to return to the brutal, decadent, and authoritarian clan of old, meets a horrifying fate.

All of these stories end up on the side of the new, often throwing their moral weight behind collectivity and compassion (though the ending of “Betrayal” is a bit more complex). But all of them build their dramas around the implications of social transformation, of what it means when rebuilding is, itself, contested. In so doing, they evoke the principle that James Mendez Holdes, a cultural consultant for Dragonstorm, outlined in the set’s Building Worlds video: monolithic representation “is useful if you want to describe a group really quickly or in a single sentence, like, ‘That’s the Mongol Horde,’” but “each of these clans has to inspire years and years of stories, so not everyone in one clan can be the same, otherwise you won’t be able to tell any more stories about them after you’re done, and we want Tarkir to persist beyond just this set.”

Although this set's ostensible drama is the titular Dragonstorms, the real thing it focalizes is something else: what it means for a world to find itself anew.

After the End

If you read the perennially crotchety forums dedicated to Vorthos writing, as I do (in turn, I sincerely recommend that you do not), then you might have encountered some angst about this off-screen change—not so much over its representational politics as over its actual representation. Why, such criticisms asked, didn’t we see this happen on the cards? This should’ve been told in blocks! Etc. etc. etc.

It’s not my job to be an apologist for Magic’s sometimes uneven writing, but there’s an undoubtedly interesting effect to the focus on Avishkar and Tarkir rebuilding rather than the revolution-in-progress. Doing so pushes against the hegemony of The Big Battle, as a narrative chronotope, and allows us to attend to the veins of activity pulsing through the worlds themselves. After the tentpole maximalism (and mixed reception) of March of the Machine, do we need another epic battle?

Could it be possible, instead, that we might find fuller worlds, more alive worlds, in what comes after?

My friend made a comment recently. "Everyone's always smiling." He meant characters in the art, and I thought first of Elvish Refuler. I think your insights here (which continue to amaze and inspire me) are part of what he was feeling. DFT and TDM feel celebratory in ways earlier sets haven't. That exuberance, as you point out, hinges on the societal rebuilding of their settings and yeah, they are smiling a lot! I would too if I survived a Phyrexian invasion or escaped draconic subjugation.

Every one of your articles has been an absolute banger. Thank you for the incredible, thought-provoking commentary. They're helping me to Vorthos-hood in ways I can't quite explain. You rock.