Both in advance of my next article and because I’ve been driven by a blind frenzy to make sure that we see more wonderful Magic stories, I encourage you to give a read to the astonishingly good Edge of Eternities web fiction.

Come close. Quiet down. Open your ears.

I decided this week that I wanted to listen a little more. This desire emerged, in the first place, from an impulse to pay attention to the thrum of my lifeworld; it’s a cliche that we’re bombarded by sound all the time, clawed by audio that gropes for our attention, so on and so forth, but sometimes it is good to quiet down a bit. But doing so is especially important in the Magic scene, where metaphorical and literal noise constitutes so much of the product lifecycle. It’s a little hard to hear what’s around me over the din of content, video, voice, words—commentary and reflection and previewing and marketing and so on.

The same is true of physical noise, the vibrations that tune our bodies to the existence in which we’re suspended.

And so I decided to think here about the sound of Magic. What does a game, ostensibly made up of pixels, brushstrokes, printed text, and cardboard, sound like?

The Sound of Rules

Language is a machine that only works when it is used—written, read, and, importantly for us, spoken. What makes up a game of Magic but a whole bunch of linguistic rules? And what is a rule without its enunciation?

What I mean is that in an in-person game of Magic, and many virtual ones as well, things happen by virtue of being read and then spoken. My opponent does not know what’s in my head, and so when I play a card, it would be more than a little impractical for them to come over to my side of the table, squint at the card, interpret it, nod their approval, return to their side of the table, respond, and then prompt me to repeat the process. The supremely elegant, entirely simple solution is for me to read it aloud: “I’ll play Serra Angel. It’s a 4/4 with Flying and Vigilance.”

But reading cards aloud is more than just a time-saving strategy, isn’t it? We use our voices not just for information but also for performance: “Serra Angel” happens, as a game event, in my enunciation of its name and mechanical ability. And it can only do so through the unique particularity of my voice, my way of speaking, which—of course—never does anything so simple as read rules-as-printed.

My voice booms triumphantly, for this card is, and by virtue of my confidence becomes, my ace-in-the hole; my voice trembles with uncertainty, constituting the card as a desperate final effort in my downfall; I speak with an attempt at absolute neutrality, trying to fly under my pod members’ respective radars by rendering this card as an inconspicuous non-event; and so on. To be sure, there are objective realities here beyond such human meanings, game states are dictated by the actual cards in a deck. But tone does affect the game’s experiential texture, may even subtly influence its course. The card is an instrument played, in its various pitches, by my voice.

Indeed, game-sounds are noteworthy precisely for the complexity they add to a game. Not every card is so simple or self-explanatory as Serra Angel—as Rhystic Studies has previously discussed, there’s a whole host of cards that refuse straightforward explanation—and the sonic minutia of our speech affects what this complexity feels like.

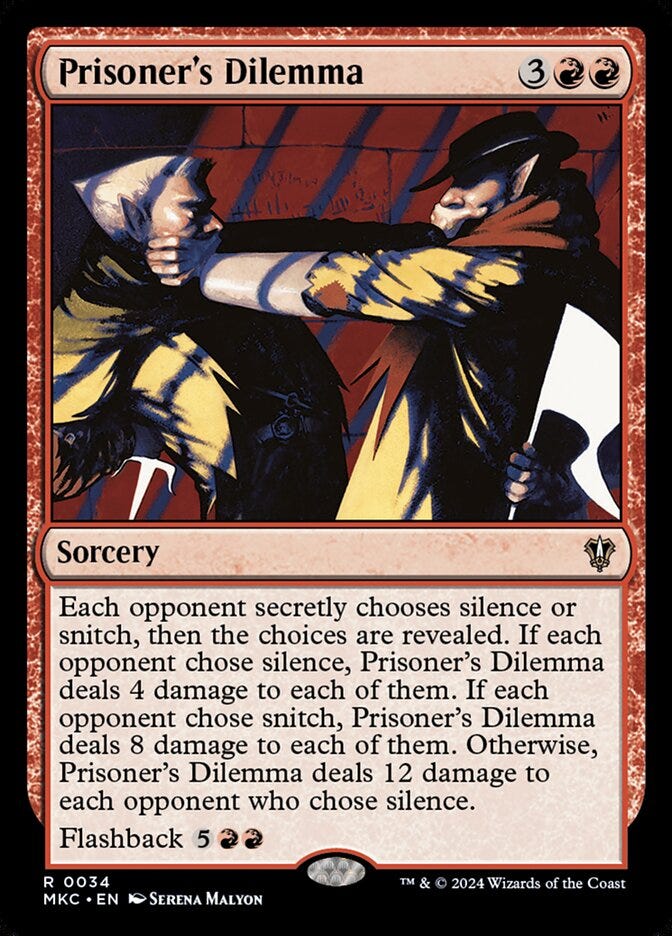

Is “Thromok the Insatiable” and me, the player deploying it, an abstruse nuisance or a sophisticated mind? Is a card like “Anafenza, Unyielding Lineage” an emblem of mechanical elegance or of regrettable power creep? Is “Prisoner’s Dilemma” a fun extravagance or a muddy dross? It all depends on the clarity with which I enunciate my words, the pace by which I measure my breath, and the control I exert over my tone.

These sorts of situations become further complicated given how many game actions are necessarily reciprocal, depending on confirmation as much as announcement. When I send attackers, I (generally) need my opponent to verbally announce their blockers for the phase to proceed—a simple enough process, but whether this attack feels like business-as-usual or some kind of strange social offense depends entirely on whether my opponent speaks with cool poise or gives a loud, stung sigh. Among the worst games of Magic are those plagued by some unspoken-but-nonetheless-expressed enmity—speaking with hard irritation when the game goes against you, snapping at an opponent when they’re trying to speak, even going dead silent when you get frustrated.

Indeed, the particularities of speech can have in-game consequences. Take the delightfully well-designed “Betor, Kin to All,” whose effect hinges on a fairly intuitive but mechanically finicky ability related to intervening-if clauses. Regardless of the rules’ technical function, the rhythmic pattern through which I speak these rules will impact how the table understands them, and in turn how they act.

At the beginning of your end step, if creatures you control have total toughness 10 or greater, draw a card. Then if creatures you control have total toughness 20 or greater, untap each creature you control. Then if creatures you control have total toughness 40 or greater, each opponent loses half their life, rounded up.

The way that I do or don’t put stress on these italicized words will affect whether my opponent (or me) perceives them as discrete abilities to which someone might react or as a single ability with a narrower response window. If I should place excessive emphasis on Then, an opponent might, even if wrongly, take this to mean that they can cast a spell to reduce my creatures’ toughness; I’ll clarify, but by then they will have tipped their hand, and public information will have altered. Indeed, I even tricked myself this way: my enunciation had so convinced myself that I tried to trigger “Tree of Perdition” in between the second and third “Then if,” which wasn’t allowed—and I lost the game for it.

This is a complex example, but the principle holds for a rang of situations. Say I mumble a card’s name but clearly enunciate its effect—my opponent, perhaps not paying full attention, as people inevitably do in the real world, might think I’m only activating an ability, and will hold off on the “Counterspell” they have in their hand. Say you’re in a commander game and another player announces they have a killspell, then asks advice on which creature to target; might the force of your suggestion influence whether it’s your creature or an opponents that leaves the battlefield?

This is to say nothing of the way that rules can be tweaked, condensed, made into shorthand. When I play a certain 4-mana artifact creature, do I need to say “When this creature enters, you may search your library for a basic land card, put that card onto the battlefield tapped, then shuffle,” and “When it dies, you draw a card”—or do I just say “Sad Robot?” Do I really need to tell you that this creature I’m playing will be sacrificing itself to get a basic land, or need I only say—and be followed by a chorus at the table—“STEVE!”? Such examples elucidate that, although rules are the genetic code of Magic, they are not its ultimate determinant—it’s voice, the performative event that enacts a game rule, even without its needing to be spoken.

To whatever extent that a Magic game comes into being through rules, through the explosive preponderance of text, it does so through, and is indelibly shaped by, the sound of the voice.

Physicality

But a Magic card doesn’t belong only to the buzzing virtual reality of speech, does it? If it did, then we would’ve abandoned cardboard and moved to exclusively virtual Magic long ago. There’s something incarnational in them, belonging to the world of sight and sound and sensation.

Let me set the scene of Magic, set in the key of what Olga Tokarczuk calls the fourth-person.

You are sitting at a table in the game store, playing a game of Commander. Your fingers reach out, feel the electric buzz of incredibly intimate atoms tugging on each other, hear the shuffle of plastic against plastic as you pull the card up. Your eyes absorb light and pass that light along to your brain and your brain perceives, among other things, a pattern that conforms with an elaborate code that it has been learning since birth, and it feels itself compelled to respond. But in order to turn knowledge into action, input into output, your brain must arrange for organized rhythmic electric pulses to travel down your spine and through your nervous system to command your vocal cords to thrum out particular vibrational patterns through the air, which pulse into nearby eardrums and are themselves passed through other ears and into other brain and are recognized as speech.

All of that takes place in about three seconds, and what you’ve done is draw a Mountain from the top of your library and announce that you’re putting it into play.

This exercise may seem abstract. But it throws into relief the way that for all the enormity of Magic as an intellectual achievement, it is also a system of bodily sensation. As the eminent media philosopher Marshall McLuhan suggests, (in a quote I’ve shared previously) “the personal and social consequences of any medium—that is, of any extension of ourselves—result from the new scale that is introduced into our affairs by each extension of ourselves.” That is to say, what a thing means is, above all, how it orients us in the world. The significance of Magic as a “medium” is that it rewires the nervous system itself, organizing our sense of speech and hearing around the affective rhythms of mana and +1/+1 counters and priority, of shuffling plastic sleeves and clattering dice and ambient noise.

What I mean is that, even as an intellectual system, Magic never stands apart from our perceiving bodies, an object to be taken up. Much as it compels us to think, it is never divorced from our embodied existence.

And what does that mean, in turn? It means that all the reticulations of reality that compose Magic are, necessarily, entangled in our very bodies as well. To adapt McLuhan’s memorable words about the “electric age”: “our central nervous system is technologically extended to the whole of mankind[,] and to incorporate the whole of mankind in us, we necessarily participate, in depth, in the consequences of our every action.” All people “are now involved in our lives, as we [are] in theirs.” My nervous system, the system that produces the sounds that make up a game of Magic, is bound up with the harvesting of trees to make paper, with the maintenance of machines that pass of electrons through circuits to display the images on that will be impressed upon cardstock, with the carbon-emitting transportation systems that take them across land and ocean and bind them into foil-lined plastic packets, and with the whole network of labor relations including manufacturing and stevedoring and lumberjacking and salesmanship and mercantilism and art and design and more and more and more. Speaking and hearing the words “I play a Mountain” plugs you into this network; the game does not make you slip free from the world but rather embeds you more deeply in it. Sound metabolizes the game into our being.

So listen up: Magic is inside you.

You Had to Be There

Although all the sounds I’ve discussed are minute, there are some that refuse identification entirely. Not because they border on unnoticeable, as the sounds above do—rather, because they belong to the sanctity of private experience.

Once I settled on sound as my topic, my plan for this article was going to be the enormous range of calls-and-responses, inside jokes, and serialized comments that fill up the three-or-so hours I spend playing Commander each week. We say “Sad Robot” and “Steve!”, but we have a whole host of others; at my last play session, which doubled as field research, I counted about seventeen in a forty-five minute span.

And I’m not going to share them.

This hadn’t been my plan. I had thought that the best thing you could do with the little drops of experience that comprise reality, as Alfred North Whitehead calls them, would be to preserve them. But as I collected examples, that aspiration felt more than a little perverse. It isn’t terribly interesting to hear someone else’s in-jokes, because they’re precisely that: in-jokes. Need a sound be shared to be real? Isn’t there some tender warmth in evanescent privacy?

(Trust me, though, we’re really funny.)

Such private sounds fill up a Magic play session. The noise of the body, the muffled cough or not-so-muffled sneeze; the personal confession; the shared joke that has been reiterated so much as to have become something different than it ever was; the eternal awful silence of a pun that doesn’t land; the opinion that, you suspect but aren’t entirely sure, was plagiarized from the Internet; the exuberant greeting when someone comes in, the sad sigh when it’s time to leave. We could, theoretically, describe these little sounds in structural terms in the same way we earlier did with game rules, but to try to grasp any one of them, outside the bounds of their private lives in any case, is to lose them.

This is to say that for as many sounds constitute Magic as a physical event or ludic process, there are more that thrum beyond the reach of our public language, existing only in the ephemeral life of that moment. Precisely in staying just out of our reach, these are the sounds that compose the social and phenomenological life of Magic, like whirring pieces in a machine larger than comprehension. If one disappeared, you might not notice, but things would not be the same.

Let me, then, take a hint from Virginia Woolf, who suggests that “words,”--or sounds, let’s say, for our case--“words, like ourselves, in order to live at their ease, need privacy. Undoubtedly they like us to think, and they like us to feel, before we use them; but they also like us to pause; to become unconscious. Our unconsciousness is their privacy; our darkness is their light.”

Next time you play Magic, take a pause. Listen for those things someone should hear about—and listen for those things that are only meant for your ears.

You have an excellent way of elevating MTG in your writing. Your work continues to inspire me to draw deeper meaning from my cards and my games. It's very rewarding