One of the terms I’ve seen most frequently in the Magic critical lexicon is “hats.”

The term is meant as a pithy and perhaps a little cynical (and perhaps rightly cynical) jab at the worldbuilding of 2024 Magic sets. The term emerged around Murders at Karlov Manor, which represented a somewhat lackluster return to the world of Ravnica. We didn’t spend much time with Ravnica’s specificity or find the world newly expanded, the fan chorus went, only Ravnica with a detective hat on. (That this feeling became so common is perhaps a testament to a short-circuit in Wizards of the Coast’s storytelling, because the web fiction and “Legends” articles seemed to point to a Ravnica recovering from the ruin of the recent Phyrexian Invasion).

Perhaps telling of the problem, the next 2024 premier set was Outlaws of Thunder Junction, whose aesthetic inspiration boasts another iconic hat, the Stetson. While the set was ostensibly meant to put a thematic spotlight on some of Magic’s greatest villains and renegades, the half-realized story and the dearth of public worldbuilding articles meant that, for as much love surely went into imagining Thunder Junction, the plane appeared as nothing more than Magic with Cowboy Hats.

Thus, “hats.” The phrase “world of hats” has become shorthand for describing a frustrating trend in contemporary Magic aesthetics: instead of pastiche aesthetics that productively remix their inspiration (as Ravnica does with Central Europe or Ixalan does with the cultures and religions of Mesoamerica, Spain, and the Caribbean), some recent worlds have felt like mannequins with superficial accessories bolted on.

Duskmourn, in some respects, runs this risk. As Donny Caltrider remarked in a recent article, it has all the trappings of a “‘Magic but make it (blank)” set.” And indeed, one of my least favorite elements of Duskmourn is the number of cards that don’t rise above the level of reference--“Here’s Johnny,” but on a Magic card.

But I think there is something in Duskmourn that does more than “hats.” In the fragments shored against the ruins, there’s the essence of something real.

And so this article is not, in fact, an article about hats.

It’s about eyes.

The Eyes Have It

Eyes, the cliche goes, are the window to the soul. But the power of the eye is deeper than truism: as the psychologist and affect theorist Sylvan Tomkins suggests, eyes are indices of about our psycho-physical feelings: Tomkins identifies symptoms of the “Fear-Terror” affect in “the raising and drawing together of eyebrows, the tensing of the lower eyelid as well as the opening of the eyes” (237) and signs of the “Distress-Anguish” affect in “arching of the eyebrows which accompanies crying…[which] leads to engorgement of the blood vessels in the eyes.” (109).

It’s perhaps no coincidence, then, that eyes are recurring characters in the visuality of horror. Francisco Goya’s Saturn and Ilya Repin’s Ivan the Terrible stick in my mind as some of the most vividly terrifying works of high art, specifically because of the eyes—soulless, evacuated, shattered.

So too in the filmic horror from which Duskmourn draws inspiration: in Rosemary’s Baby, all we see of Satan as he assaults Rosemary are his hateful burning eyes; in The Shining, Jack Nicholson’s blank stare is the first sign of his encroaching madness; Jason Vorhees and Michael Myers are most unsettling because they seem to have no eyes at all, only mere voids; Regan MacNeil’s transformation from ordinary girl to demonic conduit in The Exorcist is marked by a shift from warm dark eyes to sickly yellow to bone white.

In Duskmourn, joining this tradition is Boilerbilges Ripper.

For all the macabre and gruesome imagery populating Duskmourn, it was the Ripper that first caught my eyes. Not just because of his infernal silhouetted frame; not even because of his wide toothy smile. It was because of the tiny pinprick eyes in Kai Carpenter’s painting.

Though the eyes are easy to miss among the sanguine red of the card frame and the hellish shadows in which the Ripper is wrapped, they float there in the center of his face like two distant stars. For all the heft of the Ripper’s burly body and the density of the fog from which he leers, it is the eyes that mark his being, his intention, his spirit. Those eyes, hypercondensed into tiny points of white light, are not human eyes. They have the fixation of human eyes, the animus of human eyes, but not the soul of human eyes. What perhaps was once a soul is something else. Horrifically alien but dimly familiar.

Savoring Boilerbilges Ripper’s art helped me notice just how common eyes are in Duskmourn’s art (if last year’s Phyrexia: All Will Be One was the banner set for teeth, eyes that have taken center stage here)--and how many different kinds of eyes there are to see. The Ripper, as it turns out, represents an intriguing place in the optical spectrum (so to speak) of Duskmourn. His eyes represent the inflection point between once-human and entirely inhuman.

The Look in Your Eyes

Closest to the Ripper on the human side is Johann Bodin’s Cackling Slasher, which, like the Ripper, has deeply sunken eye sockets, tiny white eyes, and even tinier pupils: constricted pupils intently, focused on their targets--on us--like the eyes of a hungry animal. If his type line says “Human,” this is a mere technicality: amidst the strange contortions of his posture and his mangled arms and, the only sign of life lies in the recessed orbs in his skeletal mask (or is it his face?)--but there’s no mercy to be found here, only a single-minded animus.

Ever so slightly more human is Zezhou Chen’s Sawblade Skinripper. Though Chen’s harsh surgical light throws the bloody red of the Skinripper’s equipment into relief, the painting’s real power comes from the eyes imprisoned beneath her mask. Dark irises against eggy white. She is methodical; she seems not to perceive what’s in front of her beyond its mere presence; she is drive and drive only.

Nino Vecia’s disturbing mirth conveys something different—emotions more distantly human, perhaps too human. Vecia’s painting is exceptional for its composition: curved lines are everywhere in this piece, from the swirling eldritch architecture around the human (?) figure to the wound-turned-mouth exposing its brain to the wrinkles of the brain itself to the sharp curves of its brow--but the focal point is the horrible hellishly lit eyes, which feel entirely too alive for a creature whose brain is exposed. The figure looks out at us with some hideous desire, a desire of which we are the object but whose desires themselves remain empty.

Is There Something in my Eye?

On the other side of Boilerbilges Ripper spectrum are the inhuman eyes: past the threshold of feeling we might call human, where eyes become signifiers of something else.

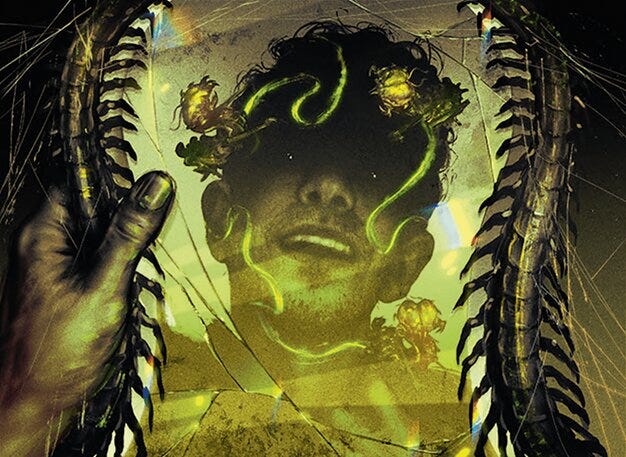

The figure in Sam Wolfe Connelly’s Say Its Name marks this transition well: in a cracked mirror, a person lit in sickly green stares with something like lust or intrigue or attraction, their face darkening so much that their humanity seems nearly erased. The only lights in their eyes are—like the Ripper—pinprick white, like the last shining reflection of humanness about to be consumed by the inhuman forces of Duskmourn.

Past this threshold are the cards whose whites, irises, and pupils have been replaced entirely by flat expanses. Victor, Valgavoth’s Seneschal (Jeremy Wilson) is ostensibly wearing spectacles, but there’s no human feeling or meaning behind them—just a glowing blankess, a sign of thrumming consuming emptiness. Splitskin Doll’s (Diana Franco) button eyes seem to be cracking and bleeding in a wide blank stare; In Silent Hallcreeper (Joshua Raphael), misshapen humanoid extremities and sunken blue glow orbs signal something with only a passing resemblance to flesh and blood. Orphans of the Wheat (Julie Dillon), whose art well exceeds the card’s shallow pop culture reference, focalizes the emerald eyes—wide open but lacking in feeling—of the titular children. Wilson and Franco and Raphael and Dillon exhibit a kind of fearful emptiness, the sense that when you look out in fear, what stares back is—nothing.

There are cards that are all eyes: Abhorrent Oculus (Bryan Sola), Creeping Peeper (Maxime Minard), and Fear of Surveillance (Jana Heidersdorf) all, to varying degrees of unnerve, foreground what it looks like when eyes loose themselves from the face. Suddenly, they’re no longer indices of our primal emotions, as Tomkins suggested. They are instead the starting points for heinous free associations: in Sola’s painting, an iris becomes pincers and a pupil becomes a maw and threads of color become teeth, ready to devour, lacking entirely in meaning.

Duskmourn’s greatest terrors are so terrifying precisely because of these inhuman eyes. Overlord of the Balemurk (Babs Webb), an image spun out of a hallucinatory nightmare, holds my attention not just because of its twisted physiology or imagery that slips free of human meaning (though those help). No, it’s because the thing has eyes. Two beady eyes peer out from twin equine skeletons, empty and inert, and in the center, a single brown eye, like one shorn from a human socket, looks out, unimpeachable, unreadable. It looks at you not without meaning. Worse: with meaning, only a meaning you can’t possibly grasp. What could it do to you? What could it want? There might be answers behind the eye, but we cannot know them.

And who are we, that are being looked at?

Perhaps the answer lies in one of the most perfect pieces of art in Duskmourn, Domenico Cava’s Murder. In Cava’s composition, the rippling shadow of a Razorkin knife traces a line across a soon-to-be-victim’s face, but what grabs my attention is the little inkling of light within the victim’s pupil, drowning in a dilated eyeball itself made tiny against the milky eye itself. The wide-hanging mouth, I think, almost oversells the image; indeed, if you cover the victim’s mouth with your hand and look only at their eyes, you may find yourself sincerely unsettled.

Why should this startle us? It’s not as though death or violence are uncommon to Magic. After all, one of the basic game actions is to kill another player’s creatures. But there’s something in this Murder--something in the eyes of Cava’s painting--that throws into relief the unspeakable intimate horror which the card’s mechanic pantomimes. This is the primordial response to violence, the reaction that is not rationalizable by card game, the emotion that slips out when we’re confronted by a profounddanger that acts less on our minds and more on our nervous systems. This Murder strips murder, the word, of all its abstractions, and rivets us to the singular moment of fear that precipitates violence. This is the ur-image on which horror is founded, the moment where an encounter with that thing outside of us shreds our outer layers and reveals us as fragile and fleshy.

If eyes are windows to the soul in poetic cliche, then eye imagery is the window to Duskmourn’s soul, beneath its sometimes-too-obvious references and its superabundant macabre.. In these eyes that Duskmourn lifts itself from the trash-heap of “Magic but make it 80s horror.” In the eyes, in the expressions, in the raw humanity and inhumanity, Duskmourn’s art calls forth not the mere pop culture imagery of horror but the human referent upon which the genre is based. It asks us to dwell in the moments when our eyes meet the unseeable.

Great article- thank you for finding more than is on the surface. I'll now remember Duskmourn for eyes as well