At the top, here, I’d like to entreat you to give a visit to MTG.wiki, the Scryfall-run Magic encyclopedia. The site contains all the same wonderful work and information as the MTG wikia site, but—far better for both my impatience for spam and my computer’s speed—it’s not operated by Fandom. Give it a visit.

If I asked you to imagine a wizard, what would you picture? Would they be shooting lightning out of their fingertips, or blasting a flame from the tip of their staff, or staring into an orb to see the future? Would they be wizened and sagacious, or would they be young and daring?

No, wait, that isn’t important. There’s a far more important question.

What would they be wearing?

In the high fantasy genealogy that precedes Magic, stretching back to the art direction of Dungeons & Dragons and The Lord of the Rings, the wizard is one prong of the protagonistic holy trinity. Although the second of three, the Warrior, is most often at the front of any adventuring party and the third of three, the Rogue, exudes enough pure cool to keep stories afloat, the Wizard provides the clearest indication that what you’re dealing with is high fantasy, neither low fantasy (where magic is rare and often malevolent) nor medieval realism. The Wizard is the narrative and artistic channel through which the audience accesses and understands what the supernatural means in a given world, whether systematic and cool (as in D&D), whimsical and amorphous (as in Terry Pratchett’s Discworld books), mystical and philosophical (as in Robert Jordan’s The Wheel of Time), or primal and mysterious (as in Steven Erikson’s Malazan Book of the Fallen series).

This pedigree carries through in Magic, which is made of and from wizards. The Wizard is the second most common creature subtype in Magic—and if we eliminate the “Species” types, like Human and Elf, the Wizard stands as the most populous of the remaining “ Class” types, narrowly beating out Warrior and sitting comfortably ahead of Soldier, Cleric, Knight, and Shaman. This glut is both a testament to the Wizard’s influence and an indication of how hard it is to get a sense of what, exactly, the wizard of Magic is (and it’ll only get harder with the game’s forthcoming expansion to the space opera genre in Edge of Eternities).

My suggestion is that in a gestalt medium like this, we can only know so much about the wizards from the spells they sling or the words they pronounce. Magic is a largely visual medium, so we get to know more about wizards—and thus the magic of Magic—based on what they’re made to look like. And we can see that above all in how they dress.

Timeless Tapestries

If you’re a fan of old-school fantasy, the “traditional” wizard outfit might be the one that popped into your head at my initial prompt. This is the “Old man, white beard, pointy hat, cool colors, maybe a symbol on the robes” kind of wizard. This image is, in fact, precisely what we see in Alpha’s “Fastbond” (Mark Poole): a purple-clad wizard, his hat curving in a gentle crescent that echoes the moons speckling his robes.

Similar Merlinesque wizards would dot early Magic releases, like Dan Frazier’s “Apprentice Wizard” and “Xenic Poltergeist” and Kaja Foglio’s “Magus of the Unseen.” These sorts of outfits are so ingrained in the fantasy imaginary that it’s difficult, at first glance, to appreciate them aesthetically; they’re pure signifiers, not summoning something new but evoking of something you already know. But Frazier, Poole, and Folgio are not such workaday artists that their illustrations are meaningless; their images cohere meaning even below the fairy dust of familiarity.

If we imagine ourselves as utter novices to the notion of fantasy magic, we can see how the garb of Frazier’s avuncular wizards—pointed hats and loose, cool-toned robes printed with symbolic patterns—position magic-users in an intriguing social niche. They are dressed in the bright colors and puffed sleeves of medieval/Renaissance European nobility, so they are not commoners, but their clothes are unfit battle and do not command authority, per se. The background wizard of “Xenic Poltergeist” is wearing a loose robe that billows over a medallion, sash, and baggy pantaloons--melding the visual language of a Catholic priest’s cassock and a Buddhist monk’s kasaya. This kind of wizard, and thus this kind of magic, is a social stand-in for clergy, of a sort: set apart from society, representing its fringes even as it remains legibly prestigious.

This is not to say that the traditional outfits only recycle older tropes. There’s aesthetic innovation to be found, for instance, in the wizard of Poole’s “Fastbond,” who wears a flowing purple fringe around his shoulders—amusingly uncool and yet incredibly cool-looking, shifting like the wind he seems fit to command. Foglio’s cheery wizard, similarly wears stunning sapphire robes trimmed with golden brocade and studded with cerulean beads that look like currents of seawater. Her robe droops off one shoulder, drawing the eye to her flowing blue and gold embroidery. Even lacking explicit symbolism, the wizard’s outfit channels a sort of elemental power suffusing her being. If this wizard evokes clergy, she does so by foregrounding the strange and striking and often beautiful ornament with which we adorn holy figures.

Nor are traditional wizards to be found only in Magic’s earliest days. Zara Alfonso’s “Lat-Nam Adept” and Mark Zug’s “Cabal Patriarch” offer, through their clothing, even more views into the social role of the wizard and their power.

Although Zug’s Patriarch takes up only a third of the frame—backlit by ghastly sculptures that remind one of guts and teeth—the eye is really drawn to the Patriarch’s grotesque clothing, a supercharged version of a medieval authoritarian like Claude Frollo of The Hunchback of Notre Dame (himself originally a clergyman, but changed to a civic official in the Disney film whose art direction seems to draw from the same cultural well as Zug’s painting). Gone is the simplicity of Frazier’s wizards or the elegant filigree of Foglio’s. Instead, the Patriarch is bedecked in grotesque and ostentatious ornaments, from his oversized striped sleeves to the intricate filigree of his chestpiece and medallions to the hat that stretches his silhouette to the top of the frame to the protrusions and rippled fabric that obliquely evokes a skeleton’s bones. It’s difficult to determine which is the top layer of the Patriarch’s outfit, which is perhaps the point: for him, wizardry means being shrouded in dense, loud, absorptive ornament.

If layered excess implies a wizard’s dark, authoritarian power in Zug’s illustration, then in Alfonso’s “Lat-Nam Adept” it means open, esoteric mystery. The key difference between the paintings, it’s easy to see, is color: Zug works in heavy black, sanguine red, and burnished gold, while Alfonso works in cosmic indigo, soft white, and seafoam blue-green. Alfonso’s Adept is bedecked in layers of fabric, like the Cabal Patriarch, but their cape drifts lightly in the wind and curls intricately around their form-fitting tunic. The composition in general and the outfit in specific are composed of downward slanting lines, like an upside-down V; Alfonso organizes the entire painting around recurring pyramidal lines, from the streaking lines on the adept’s forehead to the periwinkle-purple lines that etch down their chest, their arms, and their waist. The effect is to weave (literally) the outfit with the sense of movement, dynamism flowing through the Adept’s being. Where the Cabal Patriarch’s clothing signals an unimpeachable, immovable power, the Lat-Nam Adept offers a view of the wizard as mystic, as effortlessly elegant, as moving in sync with the patterns of the universe itself.

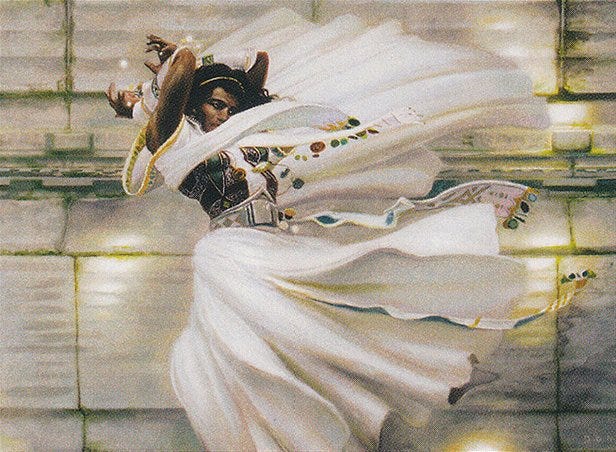

The apex of traditional wizard imagery comes in Brom’s “Keeper of the Dead” and Donato Giancola’s “Bant Battlemage.” Thematically, these paintings represent opposite ends of the wizarding spectrum, the former a dark mage who seems to be channeling the void itself and the latter a mage of the light who seems to be a conduit for holy magic. What’s especially interesting is how the wizards’ respective robes function in these paintings: both seem to envelop their wearers, to materialize their pure power . The ebon robes of “Keeper of the Dead” are nearly indistinguishable from the inky darkness surrounding her—indeed, her bony skin is the only place where light seems to land. If you look closely, you can see that her cape blooms out to the edge of the frame, but it still remains only-just distinguishable from the cosmic vacuum around her. Her robes are neither ornamental nor marks of social power, but rather manifestations of the power that she binds—or perhaps that binds her.

“Bant Battlemage” plays the same tune, but in a different key. The mage’s body here is effaced, sucked into the dynamic motion of her wind-blasted robes, which spray arcs of fabric toward the right side of the painting. Invisible are her legs, her hips, her collarbone, her shoulders, part of her face, most of her hair; they blend into the sweeping lines of the alabaster robes. Like a magically inflected Richard Avedon picture, Giancola’s painting here blurs the line between bodily and sartorial, making the wizard’s entire form motion itself. As with “Keeper of the Dead,” the robes mark the mage’s connection with a power beyond her, a power that threatens to efface her individuality—or, in this case, perhaps uplifts her beyond it.

Sorcerer Couture

At the other end of the spectrum from the traditional wizard is the couture wizard, the mage whose look blends arcane imagery with the esoterica of high fashion. These outfits imagine wizardry not through the mysteries of the monk or the authority of the cleric but through the sublimity of art.

It’s impossible to talk about this version of wizardry without reference to the Prismari, the Strixhaven students who learn magic as art and music. Standout Prismari paintings include Zack Stella’s “Elemental Expressionist,” Jason Rainville’s “Uvilda, Dean of Perfection / Nassari, Dean of Expression,” and Lie Setiawan’s “Waterfall Aerialist.” If “traditional” wizards like Frazier’s, Foglio’s, and Zug’s evoke the Middle Ages and Renaissance, the Prismari hurtle wizardry into the stylings of Rococo—highly ornate, limned with intense undulating lines, and popping with color, emblemized in the work of Jean-Honoré Fragonard.

Their clothes, like their magic, are supremely maximalist. Each outfit integrates multiple fabrics, patterns, and colors, as in the typhonic inferno of crimson, sapphire, cerulean, and gold in “Elemental Expressionist”’s tunic or the sapphire brocade, royal blue silk, white ruffles, and bright red embroidery in Uvilda’s jacketed dress. Ruffles abound, often in multiple layers—Uvilda’s enormous collar seems to swallow her head, while the train of ruffles at the hem of her skirt burst out like the plumage of a gossamer peacock. Although tidal waves of delicate rippling fabric have an undoubtedly aristocratic look, they strike the eye as at once light and dense, as though the power their wearers command is simultaneously feathery and forceful, effortless and overpowering, like an explosive symphony.

Prismari silhouettes are rarely symmetrical: on one arm, “Waterfall Aerialist”’s clothing curls out into two rounded loops of fabric, and on the other arm, fabric balloons out and then spirals out like a corkscrew at the elbow. Yet asymmetrical doesn’t mean separate, for cloth swirls around the body to form interlinked elements; the Aerialist’s coattails become the sash crossing their chest, which become the collar looping around their neck, which becomes the tendrils of fabric whipping away from them. Perhaps most strikingly, in Setiawan’s painting and others, clothing is inseparable from magical power: on the right side, the Aerialist’s ruffled skirt dissolves into, or perhaps solidifies from, a torrent of water on the right side.

This is magic as high fashion: to wield arcane energy, as these paintings suggest it, is to become the conduit for electric, dynamic, overwhelming, ever-shifting power, energy that doesn’t entirely make sense but that fills the senses to burst. These wizards are artists in the vein of Wassily Kandinsky, who wrote in 1913 that art’s “development consists in moments of sudden illumination, resembling a flash of lightning, of explosions that burst in the sky like fireworks, scattering a whole ‘bouquet’ of different colored stars around them.” Wizards channel the new, the dynamis of transformation that is at once elemental and human.

But the Prismari are not the only high-fashion mages in Magic. Representing a darker corner of sorcerer couture are Scott M. Fischer’s “Thunderscape Master” and Matt Stewart’s “Architects of Will,” both of which use clothing to figure the brutal and imperious side of the wizard archetype.

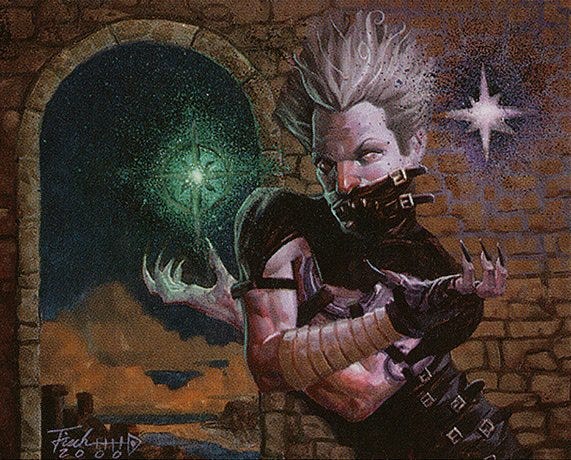

“Thunderscape Master” belongs to the Invasion Block’s foray into representing what allied color triads look like, in this case Green/Black/Red. Whereas the aesthetics of the next GRB color pairing, Alara Block’s Jund, foregrounds prehistoric ferocity, “Thunderscape Master” asks what it means for a wizard to be bound. Belts, straps, bands, and wraps ensnare their body, their waist, their chest, their arms, their wrists, even their mouth. The impression isn’t so much that the mage is being unwillingly restrained as that they’re choosing to be bound, the tight silhouette and recurring diagonal lines evoking a raw power that the restraints focalize.

We see, too, an important departure from the wizard wear of our investigation so far--skin. While the other wizards are buried in layered cloaks or covered in ostentatious fabric, “Thunderscape Master”’s chestwear actually points to the parts of the body not covered, the wizard’s trim and sinuous muscles. This clothing suggests a wizard for whom magic is neither religion nor art but a primal, almost masochistic outburst of passion—an effect certified in the card’s ability, which either inflicts pain on another player or enhances the power of the owner’s creatures.

Stewart’s “Architects of Will,” meanwhile, asks what it would look like if a wizard was also a science fiction supervillain. The pictured characters are mages from the Alaran shard of Esper, which is ruled by shrewd cyborg spymasters (thus the card’s name). These are wizards who rule, but not with the ostentaciousness of the Cabal Patriarch. No, their look embodies strange, esoteric authority. Their armor-cum-robes are, like the environment behind them, dominated by curving lines, which refuse to let the eye rest: the gold webbing on the left figure’s chestpiece lashes us up to his shoulders, which leads us up his high collar which takes us to the Etherium tracing across his skull, which takes us back to his chestpiece. Similarly, the spiraling Etherium arm on the rightmost figure twists our gaze into the lines of gold trim that sweep over his obsidian-armored shoulders; we seem to fall into a labyrinth just looking at them.

Unlike the predominance of exposed flesh of “Thunderscape Master,” there’s little skin to be found here. The high collars, besides imparting a regal air to the architects, obscure what little skin has not been converted to metal; the alternation of curves and sharp lines downplays any fleshiness or organic softness in their silhouettes. Though the painting’s figures aren’t entirely inhuman (more on that soon), their clothing casts them as menacing and conniving, unworthy of trust but also deeply powerful.

Less menacing, but still sartorially experimental, are “Spawnbroker” and “Hisoka’s Guard,” both by Wayne England. England shows a special talent, in these paintings, for making multi-layered, multi-textured clothes look like a single flowing layer. Both silhouettes are fairly clean, even if voluminous, but there are so many textures: (sick) steel blue leather, rumpled striped cotton cloth, and rough purplish bandages in the one case, and striated oceanlike fabric, midnight blue leather gloves, striped metal, and gold trim in the other. These textures seem to swallow their wearers, leaving both their faces only visible in narrow ovals.

What strikes me as most interesting, however, is the fact that both outfits imagistically parallel their vocations. “Spawnbroker”’s sharply pointed shoulderpads, the pyramidal lines separating their sides from their chest, and their high, horned hat, tipped with gold points—all evoke the uncaged dragons they’re preparing to sell. “Hisoka’s Guard,” set against the mist and forest and capped towers of the Kamigawan wizarding academy of Minamo, mirrors both the natural and built environments in his outfit. The sharp vertical lines and gold tips of his horned helmet echo Minamo’s towers, and the curving lines set the karahafu gables in microcosm--but his robes blow wispily like the breath of the mist. The couture stylings of the Guard and the Broker are not particularly practical, but they visualize a particular vision of magical practice. They are wizarding as mercantilism, wizarding as architecture; to command magic is to reflect the very magical practice in which you engage.

The Alien Arcane

If Sorcerer Couture represented the fringes of what a wizard’s wardrobe could look like, this next category goes even further, imagining what it means to wield magic in a way that’s entirely foreign to the high fantasy aesthetic—indeed, often to humanity itself.

These aesthetics tend to be dimly legible in our visual vocabularies, akin to the eerie science-fiction medieval-futurism of Jacqueline West’s work in Denis Villeneuve’s Dune films. Heather Hudson’s “Azorius Aethermage” would fit right in with that world, I think. Her bulbous silhouette is startling and strange, contrasting sharply with the relatively compact forms and sharp lines of the wizards we’ve seen thus far. If other wizards encode concrete social roles, this design switches codes: the voluminous robes evoke a judge (fitting for the Azorius), while the enormous pauldrons and rounded gauntlets evoke a cartoonish knight. But the sheer strangeness of the design outstrips even these categories; with its exaggerated size and odd shapes, it’s hard (but interesting) to imagine a wizard like this moving about in the world. This is a wizard who does not come from our reality but remains obstinately in her own.

Similarly familiar-yet-alien are the costumes in Ray Lago’s “Balshan Beguiler” and Mark Zug’s “Neurok Transmuter.” Both wear cloth that appears standard in theory, the former a navy-blue tunic and the latter a robe that blends steel blue and silver. But of course, that’s not what draws the eye in either case. Our eye is drawn first, in Lago’s painting, to the strange bony bracers and elbowpad in the foreground, then up, along the undulating lines, to the strange chest plate, shoulderpads, collar, and headpiece, all made of the same curvy osseous material. There are no context clues to suggest that he’s a hunter or necromancer; by the same token, these are plainly not animal bones, for they’re shaped as armor would be. No answers come here, only exotic evocations: skeletons, stone, the chitin of a scorpion, or perhaps something stranger.

Stranger is a perfectly apt term for “Neurok Transmuter,” in which the eye is drawn to his bizarre headpiece—a cybernetic enhancements that was everywhere in the design of early Mirrodin. Although the painting’s name implies a conventional magical act, transmutation, the Transmuter’s cranial, insectoid headpiece casts a pall of eerie, grotesque mystery over the image. Whatever this wizard is, whatever those strange markings are on his robes and whatever the nature is of his partially metallic arm, it’s are a far cry from the wizardry you know from “Fastbond.” If he is, per his type line, a “Human Wizard,” it’s only in the loosest sense.

Even further beyond the boundaries of the human are Jim Nelson’s “Scornful Egoist,” and rk post’s “Warped Researcher” and “Lumengrid Augur.” The Egoist (allegedly a “Human,” based on its type line, but rightly human only if I’m made of Laffy Taffy) retains the dimmest vestiges of human clothes just as it distorts the human body itself. Its purplish robes and high neck gaiter spiral around its body like the undulating ooze of its skin, as though an extension of its body; mere scraps of fabric linger around its wrists, perhaps sloughing off or perhaps tightening or perhaps merely hovering in place. Its chestplate seems entirely unuseful given its new gelatinous form, but our definition of “useful” is clearly not its own; what we think of as external ornament, it takes as an extension of the body.

“Warped Researcher” (which, like “Scornful Egoist,” depicts a wizard in the Otarian Riptide Project) works a similar sartorial remix. With its unsightly mutations and chimeric form, its lavender skin and hairy feathers and spiraling tentacles, it seems to be a beast with no need of clothes—and yet it does wear clothes, bedecking itself in a rubbery seafoam-green bodysuit like the HAZMAT suit of an experimental researcher. The principle seems reversed from HAZMAT, however, aiming not for containment but for enhancement. Through the ornamental crimson pauldrons and gauntlets, there thread black pipes riveted with gold, beautiful but unsettling, perhaps feeding him air or pumping mutagenic fluid into his body. One wonders, indeed, where the clothing ends and the body begins.

post’s “Lumengrid Augur” is the furthest of the bunch from wizards as we know them. Alienness here is literal, for the Augur is one of Mirrodin’s Vedalken, a species of blue-skinned amphibians. But it’s post’s clothing design that sells the alieness. There’s just a dash of familiarity here—the silhouette evokes the flowing robes of a traditional wizard—but instead of cloth we have armor plating, instead of loose sleeves we have tight-fitting leather with bulging veins, and instead of a star-speckled hat we have a glass case that insulates the augur from the outside world. Looking at the painting from a distance (at the scale of a card, say) it might take you a moment to notice that there’s a figure in the armor at all. In that brief moment between perceptions, it appears to be wizard-as-cyclopean-astronaut. Magic, the Augur’s clothes reflect, comes not from arcane tradition but from the vicissitudes of science, even as it remains an inaccessible mystery. Merlin this is not.

To be continued…

These paintings are all stellar works of aesthetic storytelling on the whole, but the work they do with clothing illuminates something fascinating about the work that clothing design does in Magic. The intricacies of an outfit can help give texture to a world, but even more, it helps produce, in the imaginative gestalt that is this game, a sense of what magic itself is.

But midway through writing this article, it struck me that there isn’t nearly enough space to talk about all the wizarding fashion I want to discuss. As such, this will be the first of two entries on the subject. If there’s some wizard wear I’ve neglected to mention, drop it in the comments. Next time, we’ll be discussing the power of the orb, the secrets of the spellbook, and the mysteries of the wizard hat.

This was a fantastic read! It's made me look more at the "costuming" of characters in cards. So much so I went back and looked at the Invasion master wizard cycle and they're all dressed in fascinating ensembles. I was also struck by David Dorman's "Blind Seer" while perusing the sets casters, and the scantily clad cycle of emissaries. That whole block was a wild ride!

Obsessed with Uvilda