Different Worlds

In my last article, I discussed my great love for Magic art that lives on the other side of the fence from realism—the goofy, ridiculous, cartoony, dumb, amazing art that can breathe life into a world. I spent time with this art because I think it offers something really quite beautiful to Magic’s world: multiple perspectives. Even in a unified world, there is always heterogeneity, difference, distinction—different ways of representing reality and different ways of living in it, experiences whose profundity and distinction might need to be represented with soaring fantasy realism or might be better articulated in the whimsy of cartoony art.

In this article, I’d like to shine a spotlight on some other artistic perspectives that lie somewhere inbetween fantasy high realism and over-the-top unreality. I’d like to savor the work of a few artists whose work is in dialogue with fantasy realism, but whose tools expand the scope of what Magic’s world is and means.

Ekaterina Burmak and Pre-Raphaelite Splendor

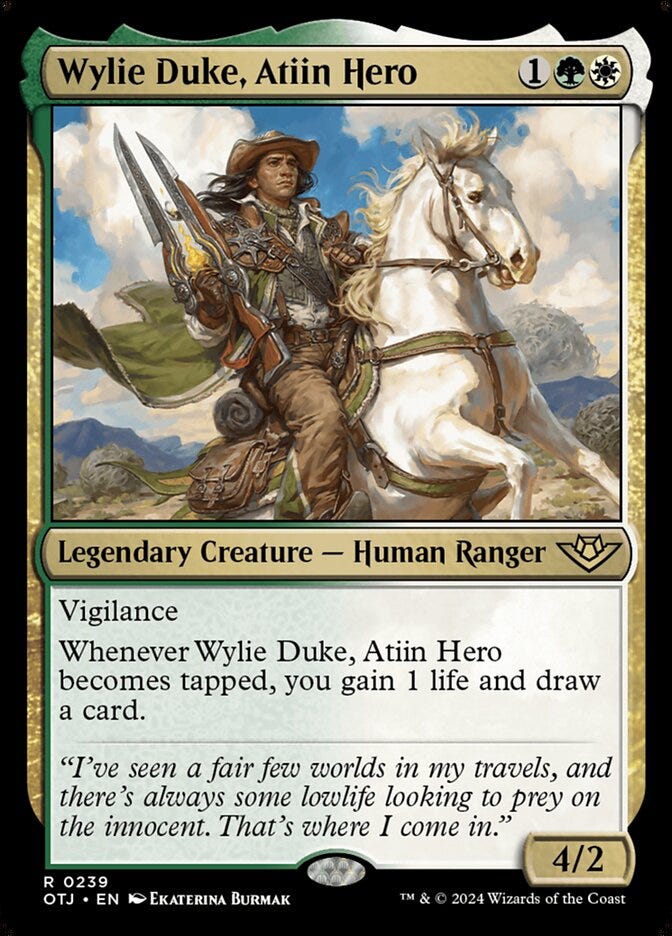

I first noticed Ekaterina Burmak’s work on Wylie Duke, Atiin Hero. I love Green-White legends, which is what made me stop to look at the card as I rifled through my Thunder Junction prerelease pack—and I’m glad I took that extra look.

Look at the subtlety of Wylie’s expression, the resolution and the sadness and something else, something like melancholy. Look at the tufts of his hair billowing in the wind and the solidity of his rifle, the way it seems like it would click and clink as it shakes in motion. Look at his pants! The folds, the ripples, the shadows, the light! They look like pants!

There’s this strange lush liveliness, a depth of detail that Burmak distributes throughout most of the painting, a special crisp precision. It’s amplified, of course, by the player’s perspective looking at it: the small scale of the card compresses all Burmak’s fine details and tiny lines, making it look crackly, overabundant with *stuff.*

I don’t know Burmak’s explicit influences, but I’m touched by her work for the same reason as I’m touched by the work of the Pre-Raphaelites, especially John Holman Hunt. The Pre-Raphaelites were a group of artists who lived in the mid-nineteenth century, and they courted controversy by departing from the conventional wisdom of Renaissance-inspired art. Whereas art teachers inspired by Raphael exhorted artists to improve upon nature, use it as a starting point and adjust it to create geometrically proportionate works, the Pre-Raphaelites staunchly supported painting directly from nature (thus their name—they sought to recover the techniques of art from the age before Raphael). The great nineteenth-century art critic John Ruskin, the greatest supporter of the Pre-Raphaelites, celebrated the Pre-Raphaelite commitment to painting the world as it actually looked, not in some idealized or imagined form. He praised “simple love with which [Hunt] dwells on the brightness and bloom of our summer fruit and flowers,” and of John Everett Millais, he says: “[He] sees everything, small and large, with almost the same clearness; mountains and grasshoppers alike; the leaves on the branches, the veins in the pebbles, the bubbles in the stream.”

This art history lesson elucidates something intriguing about Burmak. Her emphasis is not on perfect proportionality, though she’s certainly no amateur—her emphasis is on all the textured details of the world, the way cloth ripples as holy light spreads over it or the way teeth jut from monstrous jaws or the way thick cloth furls under the hot desert sun. These are small things, but those are small things that make the world of Magic feel lived in, feel real. If the Pre-Raphaelites were captivated by the real world as it appeared to our eyes, Burmak’s art points us to the way that, for the people of the Magic Multiverse, the world must look the same way.

Chris Seaman and Foregrounding Foregrounds

The next artist on our little journey is Chris Seaman.

There’s so much to unpack in Seaman’s work, especially given how many iconic cards he’s illustrated. You could talk about the way that he paints images soaked in vibrant light, like Risk Factor. You could talk about the whimsical grotesquerie of his imagery, like the sad-looking severed head in Stitcher’s Supplier or the evil pie in Old Flitterfang. Both of those, for what it’s worth, reflect Seaman’s avowed debt to Tim Jacobus, the cover for most of R.L. Stine’s Goosebumps books.

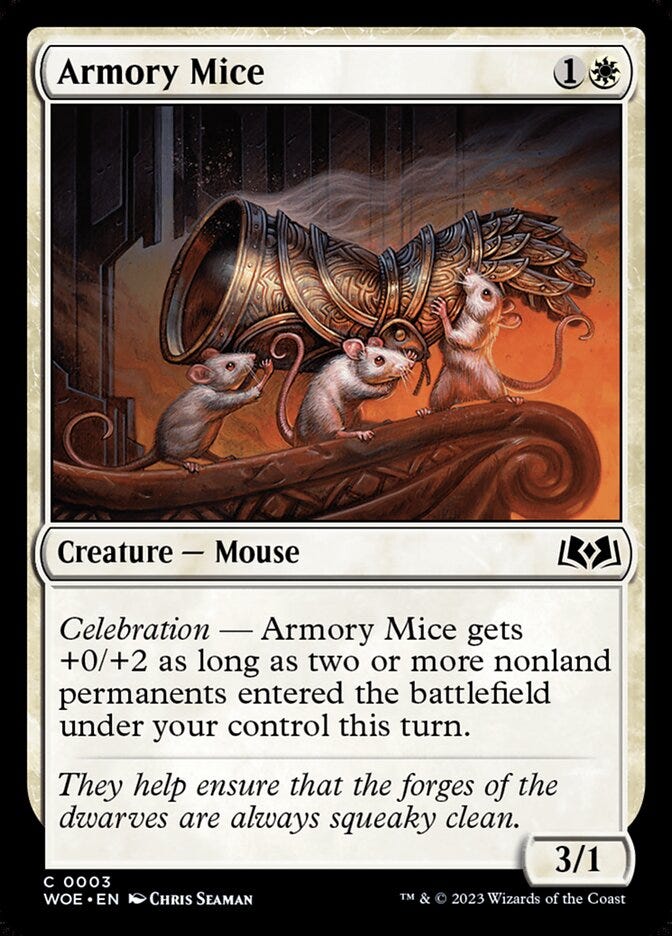

But what I find most astounding about Seaman’s work is the way he plays with the foreground and background of his work. This, too, evokes Jacobus—a great way to sell a horror book to a child is to make the spookiest-looking thing the closest thing to the viewer—but Seaman has an astonishing flexibility with foregrounds. In Armory Mice, the background is rather nonspecific—clearly, it’s an armory, but we don’t see very much, because our eyes are arresting by the notching line of the mice’s bent backs and the gauntlet’s bending frame. There is a superabundance of detail in this image—not Burmak’s kind, where it seems true to life, but another kind, something that makes this strange image feel at once real and like it jumped out of a storybook.

In other works, Seaman’s foregrounds get a little more detailed, but they remain rather opaque, always focusing your attention on the focal point in the foreground. There’s such a dense atmosphere in so many of his paintins, whether the blazing labyrinth of Kherr Keep in Rograkh, Son of Rohgahh or Rosnakht, Heir of Rohgahh or the library in Artificer’s Assistant or the Wild West town in Make Your Own Luck or the hellish torture chamber of one of my favorite Magic paintings of all time, The Meathook Massacre. These paintings feel like slivers of places, not exaclty the kind you could imagine yourself in but the kind that seem lived-in by fantastical characters, the kind where there seems to be a boundless milieu for adventures beyond the frame of the card.

But what makes Seaman so talented at evoking these worlds is how little of them he actually shows. Certainly, he picks some great images—books, pole-mounted skulls, starry skies, bloodstained walls, castle gates, even other figures—but nothing is as fully detailed as the figure in the foreground. Sometimes that figure is the character in question, like Rograkh and Rosnakht, and other times it’s an object—like the limp hooked hand in Meathook Massacre.

Compared to this crisp foreground images, images in the background are hazy and unclear; they’re also painted at diagonal angles, which makes them more snapshot images than fully comprehensible worlds. But this is the beauty: by drawing our attention to an item in the foreground, at once unimportant and also the most important, Seaman directs us to use that object to fill in the blanks of the background. I don’t know what Kher Keep looks like, but the image of Rosnakht’s improvised armor and furious disposition give me the ingredients to formulate its atmosphere in my mind; I don’t know who the Meathook Massacrer is, but the severed hand exudes the kind of cold inhumanity that helps me understand what his world is like. If artists like Chris Rahn help us see what characters are like, Seaman helps show us what their worlds are like.

Liiga Smilshkalne and the Mysticism of Light

The final fringe realist in our little examination is Liiga Smilshkalne, a Latvian illustrator who’s been working on Magic cards since 2021. Smilshkalne activates a very specific part of me: the photophile.

No, I don’t mean the part of me that loves photographs (I’m quite bad at those). I mean the part of me that loves light, which is Smilshkalne’s specialty. Smilshkalne is the rare Magic artist who channels one of my favorite elements of Magic’s world, or indeed any fantasy world: the strange, mystical sense of reality that a magical being inhabits. This kind of mysticism—the way that reality bends and warps and is fundamentally different for someone because of their abilities—is clear in some of Magic’s fiction, but it doesn’t often show up in cards. After all, how can you represent Jace’s relationship with the mind in images alone? How can you represent Wrenn reaching across the darkness of the multiverse to find Zhalfir? How can you capture Elspeth’s sudden transformation into an angel? And yet, Smilshkalne manages it.

There are more clearly representational works, like Magma Opus or Forging the Anchor, which capture the raw power of primordial energy. But there are others, like Graveyard Shift, Dream Fracture, Hell to Pay, and Lay Down Arms, whose swirling lights simultaneously evoke magical power and obscure the “real” material person inside, as though their subject is encountering a power beyond their very comprehension.

I’m especially awed by One with the Multiverse and Path of the Animist, which show singuar figures (Urza and Nissa, respectively) nearly being ripped apart by the transcendent power of Planeswalker sparks; they encounter cosmic forces the likes of which, like the golden cliffs of a faraway nebula, are more spiritual than real.

Smilshkalne goes all out in cards like Transcendent Message, Breach the Multiverse, Planar Genesis, and Brainsurge. I can’t understate how amazing her work is, here, not just visually (and it is visually amazing), but representationally: she’s presumably adapting a pretty concrete art brief, some evocation of the mood, and turning it into a symphony of flowing essence that looks like the sheer energies of Creation streaming forth into the cosmos. It would be one thing if she just drew people made out of light, but no: her paintings have a logic like Whiteheadean process theology, attendant to the ever-moving, crackling, surging, sidereal explosions of creation that constantly flow like starlit water through and between our atoms, bodies, our worlds.

I strain for language here only because Smilshkalne does that to me. She takes a world that was once unfamiliar—wizards, dragons, demigods—and defamiliarizes it further, crafting images that express the sheer vital life that courses through the essence of magic itself. Her work demonstrates that in the world of Magic, spells are not merely parlor tricks; they are the moving essence of a living universe.

I’m reaching Substack’s character limit, so I’ll be brief in my conclusion! If you feel stimulated, feel free to leave a comment or offer a thought. Next time you see a card whose art you love, think of me.