Cartoon Logic

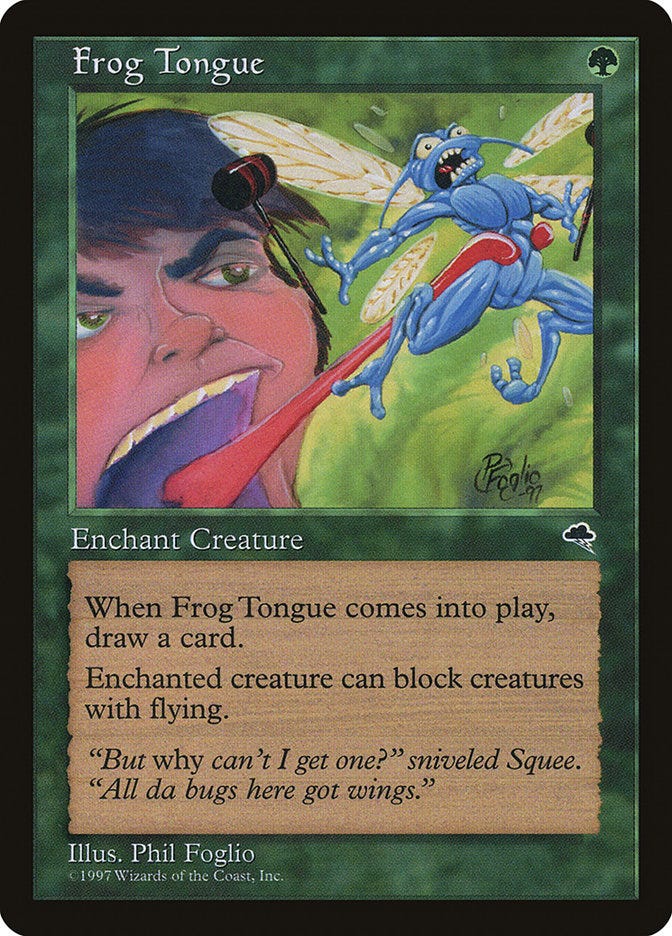

I have a pet project. A Commander Cube full of stupid, silly, and otherwise unplayable cards. There are bizarre legendary creatures, like Skeleton Ship, and support for niche creature types, like Bringers, and cards that seem from another mechanical universe, like Chaoslace. But the real centerpiece of the cube is the art, for which I’ve chosen the strangest, ghastliest, and/or funniest cards I could find. And the artists with the most representation, by far, are Phil and Kaja Foglio.

There’s an unrestrained silliness in the Foglios’ Magic work, joyful rather than insipid. Their imagery evokes Hanna Barbera and Tom & Jerry, old cartoons where physical laws functioned not according to the rules of classical physics but according to rules of resemblance—if someone hits a wall, their body compresses because that’s what any object does when it hits a wall, and when an object compresses, it becomes an accordion because accordions compress, and when it becomes an accordion, it can be played like an instrument because accordions are instruments.

If you’re enchanted to have the tongue of a frog, what else are you going to do but use it to catch unwitting insect?—and if an insect is caught, what else will it do besides yelp out in fear? If your armor is turned into insects, won’t you be wearing underwear beneath it?—And if you’re wearing underwear, wouldn’t you be wearing tighty-wighties?

Art like that of the Foglios isn’t too common in Magic anymore, which is understandable. In a landscape full of masterpiece fantasy-realist paintings like Storm the Seedcore, Anointed Procession, and Vanish into Eternity, who wants to look at goofy art like that of Infernal Darkness or Foglio’s Chaos Warp?

Well, I do.

Funny Business

Here’s a question. Is Magic funny?

I think most people would say yes. There is, after all, a wealth of comedy relief characters and humorous narrative beats and quippy flavor text lines and tongue-in-cheek Secret Lair series. But if I prodded you, you would probably agree that Magic’s humor isn’t, right now, the same kind of humor as in Lure or Orcish Librarian. It’s different: it isn’t exactly dry, but nor is it over-the-top.

There is, indeed, still plenty of humor in Magic. In keeping with the humor of contemporary blockbuster media, it’s jokey, but the jokes are couched within a veneer of realism, never violating the essential seriousness of the world. We can have a laugh, but outside of Un-sets, Magic isn’t a joke—and even Unfinity, as funny as its content and mechanics are, still maintains an essential artistic realism. Though Fblthp is sillier than Jace, their respective depictions have a shared investment in the “realistic,” in quasi-true-to-life proportion and photorealistic colors that root them in a serious world.

This kind of humor, from a visual perspective, is like the Mona Lisa chewing bubble gum, not Fernadno Botero’s balloonlike redux—realism with a silly hat, not an entirely exploded sense of the real.

I’ll let you judge which piece you prefer—but I have an enormous affection for Botero’s work. His humor is something more than novelty or parody; it takes the classical art that shapes our ways of seeing beauty and asks whether, in fact, we could see reality as big and bulbuous and whimsical and different, real and unreal at once.

Unreal Realism

All this is not to say that I have any animus against cards like those I’ve mentioned above. In fact, some of my most favorite Magic artists (Victor Adame Minguez, Magali Villenueve, and Jason Rainville) work in the fantasy realist style (And, in fairness, the Foglios’ art is hardly peripheral—the Kickstarter for the Foglio Portfolio was a huge success, and Phil Foglio is slated to have a Secret Lair coming sometime soon). But, as I will argue and argue again in these articles, Magic’s paintings are never just standalone art pieces, enjoyable for their own sake—they’re the little aesthetic micro-events through which a story world comes into existence in our minds and emotions and imaginations. And can the world be captured only in seriousness? Must all our imaginings find their homes in refined oils and immaculate proportions?

I wonder whether we lose out on something when our only humor comes from the bubble gum Mona Lisa, the one that makes you smirk for a second but then turn away and forget about it. I wonder whether some silliness, in fact, might offer a richer view of Magic’s world. We’re talking about a game with huge dragons holding big-ass hammers fighting dim-witted cyclopes and wizards who can turn enemies into monkeys—It’s serious, but it’s also deeply unserious. Maybe it’s worth feeling through the silliness of it all, imagining what it means to live funnily and gleefully in a world full of absurd things.

Nor are the Foglios the only examples of more interesting, more whimsical, more goofy art, the kind of art that shows us another world within our other world. I’m thinking of art like Mind Bomb and Amnesia, Goblin War Buggy and Jester’s Mask, Fire Covenant and Giant Strength, Stasis, All Hallow’s Eve, Fanatical Fever, Ebon Praetor, Necrite, and Bestial Fury.

One might respond, of course, that aesthetic cohesion is what makes Magic so great. Consistent art direction is the reason we can recognize that Fblthp and Jace (and Karn and Krenko and Tinybones and so on) belong to the same world, no matter how different they are. And yet, of course, the shared world is a phantasm made of our own imagining. While the Foglios’ art conjures a different world than Magali Villenueve does, Magali Villeneuve herself envisions a different world, however minute the difference, than Randy Vargas or Jasper Eising, much less expressionistic artists like Dominik Mayer and Rovina Cai. Each of their styles, constituted as they are by different aesthetic philosophies and approaches, could be representing different universes entirely.

But there is cohesion—only it doesn’t come from them, it comes from us. As I’ve argued in previous posts, Magic as a world, a game, a gestalt thing, comes into being through our experiences of interpretation. Only by our sustained activity of linking together similar subject matter, artistic motifs, gameplay, and so on—by filling in the blanks—does the world gain its wholeness. We give it life by interpreting it as living. There’s nothing about Magic that demands fantasy realism, or indeed any style in particular. True, for the game to work, there has to be some kind of cohesion, some work to link together different kinds of art—but that linkage comes as much in our acts of interpretation as in any kind of homogenous style.

And precisely because Magic’s world is partially of our own creation, forged by our own play of expectations and openness, its world can be different. I’m not saying we should jettison Magic’s seriousness, either—if my articles reflect anything, it’s that I take Magic quite seriously, including when it, too, is serious. But perhaps we’ll one day experience a plane that can be seen from many different angles, not just through realist high fantasy but through cartoony delight. Given the forthcoming art for Bloomburrow, whose art direction, homaging Redwall, seems to lean into whimsy a tad more than we’ve seen before, the prospects are good.

In the meantime, though, let me give you an invitation. Next time you’re picking up some singles for your deck, check out whether they have multiple printings. If you come across a card like Lure, with two kinds of art—both beautiful, both striking, but one a fantasy realist piece and the other an explosion of cartoony delight—think about picking the silly one. Let yourself appreciate silliness.

I’m so glad I followed the link from the Rhystic Studies site!

Thank you for the thoughtful write up! The art of Magic has always drawn me to the game and I love your thoughts on how, even with stylistic diversity, the players are able to create cohesion through the way we play.

My passion for the commander format is rooted in getting to explore the game’s vastness of art and function.

Looking forward to more of your posts!

Having played Magic since 1994, aesthetic messiness has been a feature of the game since day one. I'm glad you're spreading the good word of being goofy and downplaying the role of generically-and-competently-mimetic art in the game's identity and success.