What is Technology?

On Magic's abstruse, odd, and inscrutable artifacts

Let me repeat the title of this article: What is technology?

We’re surrounded by intuitive answers. Technology is the phone or computer on which you’re reading these words. Technology is the digital camera installed in your phone or laptop and the film camera that preceded it. Technology is the cars on our roads, the trains in our cities, the planes soaring in our skies, and the spaceships drifting through our stellar horizons (in reality and in our imaginations alike).

But there are other technologies. A hat is a technology; a clock is a technology; language is a technology.

As the techno-philosopher and granddaddy of media studies Marshall McLuhan suggests, “the personal and social consequences of any medium—that is, of any extension of ourselves—result from the new scale that is introduced into our affairs by each extension of ourselves, or by any new technology.” McLuhan’s thought is informed by his historical moment (he was writing in the 1960s, during the explosion of telecommunications technologies that directly precedes out own), but his insight is productive for us. The real meaning of any medium, which is to say the meaning of any technological instrument through which we interface with the world, resides not in its ostensible purpose but in the way it alters the human relationship with the world.

One of my most recent EDH decks—one built around “Mendicant Core, Guidelight”—has set me to thinking on these ideas in the context of Magic. As the game’s worldbuilding principles have grown richer, artifacts have taken an increasingly large role in representing the technological tools of its fantasy realist worlds. Befitting the etymology of the word “artifact,” made thing, Magic’s technology is often the sword a warrior carries into battle, the boots a daring general uses to make their escape, the powerful charm with which a wizard generates power, or the altar on which a mad scientist claims her victims. They are utilitarian tools to help us achieve our goals.

But if we think about technology as an extension of the human itself, then we migth find something more.

Metaphysical Machines

What makes a machine work, beneath its surface? Not just physically, but existentially, cosmically?

Take a car. In terms of direct causation, a car is powered by an engine. But what really makes it work is far greater—palpable-but-invisible powers like force, acceleration, and resistance. The car, too, is not just a physical object but a medium, a device that metaphysically alters the relation of the human to the world around them: it reprograms what counts as distant or faraway, it extends the nervous system with an apparatus of steel and rubber, it inheres a system of signs and rules (speed limits, lane markers, odometers, fuel gauges), it entangles users within the economic and material infrastructures of oil refinery and auto production, and more.

What might it look like to visualize these metaphysical relations in a machine? The art of Amy Weber offers a stunning answer. She channels the simultaneous simplicity and strangeness of alchemical esoterica, and in so doing she helps us imagine the metaphysical meaning latent in technology.

One of my favorite pieces of Weber’s is “Life Matrix.” If I gave you the name of the card and its mechanics and then asked you to imagine what the art should look like, you might—with the visual vocabulary of contemporary Magic in mind—imagine a glowing object, perhaps something the size of your hand, maybe glowing. Perhaps a Mana Rock.

But Weber’s “Life Matrix” is nothing of the kind. It depicts (if such an image can be said to depict anything) a skeleton suspended in a strange gyre patterned as a twirling, DNA-like double helix, shot through with pixelated distortions and orbited by shimmering copper spheres, high above a starlit ocean.

What is this thing? If you stretched your faculties for reason, perhaps you could say that it’s a chamber for regenerating the body. But such a clearcut explanation seems ill-fitting to Weber’s oddly beautiful illustration. Her art renders the Matrix as figural, metaphysical: regardless of how the artifact’s mechanically functions, what it does is refigure the relationship between the body and the cosmos, externalizing the body’s inborn generative power, fundamentally reconfiguring the physical realities that once constrained the body, and calling on powers beyond physical proximity to animate form. If we could look under the metaphysical hood of medicine, perhaps this is what it would look like.

Such is true, too, of Weber’s “Armageddon Clock.” While the card’s name is foreboding and apocalyptic, it does not depict a destructive explosion like Slawomir Maniak’s “Urza’s Ruinous Blast” or Jim Nelson’s “Pyrite Spellbomb.” Weber’s image is arcane and inscrutable: a wooden clock, laden with abstruse iconography and bedecked with angelic wings, floats before a map crisscrossed with lines and nodes. The implication, as I read it, is that the Clock is at the core of a massive network that links all these places; it is the focal point of an immense web of causation—a foreboding one, at that, given the card’s mechanical emphasis on “doom counters.”

What does this clock do? Is it the actual artifact, or merely a strange symbolic representation of a magical mother-of-all-bombs device like Nevinyrral’s Disk? Weber’s image is not concerned with such questions. Instead, it visualizes the network of metaphysical connections activated by a doomsday weapon, the way that a startlingly benign object extends the possibilities of destruction beyond the physically proximate and into the global, the geopolitical, the planetary. In this sense, Weber has created an apt counterpart to Kerstin Kaman’s “Golgothian Sylex,” whose haunting, understated detail represents an unspeakably destructive artifact that reshaped Dominarian history. Illustrations of the Sylex tend to foreground its eerie banality, affectively contraposing its status as a chip-bowl-lookalike with its unimaginable power. Weber’s “Doomsday Clock” does the inverse, asking what kinds of reshaped human relations are ushered into being by an apocalyptic weapon.

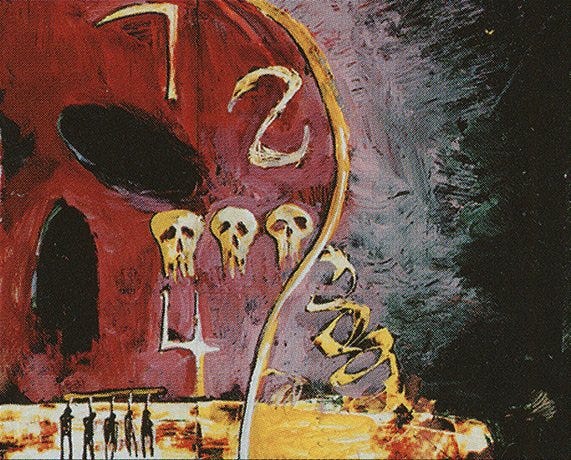

George Pratt’s “Time Bomb” offers an even more unsettling image of technological metaphysics (Weber created the card’s original illustration, which is characteristically lovely, odd, and interesting). It’s not clear what the titular device actually looks like; Pratt’s image is odd and grotesque. With its thick clotted colors and dense abstraction, it reads more like an Anselm Kiefer than the Sword of Fire and Ice.

The illustration is structured by division and subdivision: an undulating gold line, shining as if made of metal, divides a bloody red blob from streaking gray, which itself is divided by a razor spiral of gold that corkscrews into a void of utter black. The left side is just barely representational, forming a strange, oversized, gruesome clock. Within the red face lay black ovals that read like holes rent in reality; around its distorted edge runs a series of stylized numbers: a sharp 4, a serpentine 2, a 1 shaped (as Questing Phelddagrif pointed out to me) like a scythe, and three skulls in place of the number 3. At the bottom left is perhaps the most disturbing element of all: crude black silhouettes, etched with red, that appear at first to be gazing but that actually seem to be strung up by the neck, dangling lifelessly from a golden gallows.

What is the ghastly instrument that Pratt purports to illustrate? It seems that no rational explanation can obtain. Legible only is the Bomb’s metaphysical force: it recomposes the cosmos in the key of destruction, converts time to death, reality to annihilation, that evokes a description of the Hydrogen Bomb that comes in Benjamín Labatut’s The MANIAC:

“Because it wasn’t just a bigger bomb, you see, it was a true horror, something that could not be justified in any sense, an evil by any measure, a weapon so far beyond what was reasonable and rational that it was as if we had willingly wandered into the darkest regions of hell.”

In Pratt’s illustration, the apocalyptic of the Time Bomb force distorts systems of meaning like the clock, mutilates the human body, and, indeed, seems to spell doom for reality itself—on the other side of the clock, the gold foreground clears out its human figures and then plunges into an abyss. This is the metaphysical meaning on the other side of the medium, and it’s a deeply terrifying one.

Social Devices

Other odd artifacts in Magic’s canon help us to consider technology as not just utilitarian but social.

As the literary historian Raymond Williams argues, new technologies are often framed as explosions of newsness, as completely unprecedented inventions that alter the fabric of existence (think of discourse from Silicon Valley executives about how artificial intelligence will change the course of human existence). In reality, Williams argues, technology emerges as a product of social needs: tele-communications technologies, to use Williams’ example, did not simply drop out of the sky, but rather emerged in dialogue with “problems of social perspective and social orientation” of the nineteenth century. The point is to think of a technology not just by asking how it changed things but also by asking why it felt useful to society enough to be created in the first place.

Magic’s high fantasy flavor can activate these kinds of thoughts precisely by defamiliarizing us from technology. To be sure, there are still sets that lean into pastiche and homage—like Duskmourn’s evocation of 1980s television and Aetherdrift’s automobile theming—but the foreignness of the fantastical still lingers in many places.

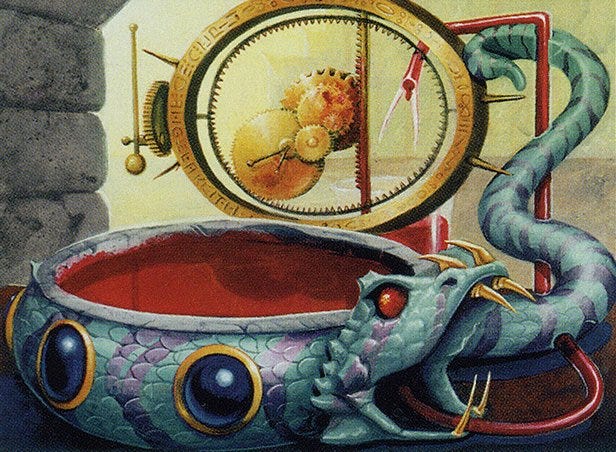

One such place is Keith Garlett’s “Blood Clock.” The artifact belongs to the world of Kamigawa, but it doesn’t seem to be inspired by any specific feudal Japanese device (if any historian of Japan knows of pools of blood shaped like snakes attached to clocks, feel free to dispute me). Instead, it’s largely foreign; we’re left to wonder, and perhaps imagine, what this strange serpentine instrument might have meant to its society, what role it could possibly have served.

The flavor text gives us a strong indication: “In an age of war, time is measured not by sand but by blood.” Its function, then, indexes a social need: the device might read as surprising and garish, but it’s all too logical for a social world in which bloodshed seems to permeate everything.

The illustration’s mixture of biological and mechanical vocabularies bears out similar meanings. It’s unclear whether the snake is a finely wrought sculpture or the remains of a living creature, but regardless of the answer, the serpent clearly been integrated with human handiwork (the inlaid gems, the arcane clock). This bowl-cum-snake-cum-clock would be nonsensical in our world, because it answers no social need—but existence in Kamigawa suggests, perhaps, that this society is one angsting over how to manipulate the biological and the mechanical alike.

Adam Rex’s gruesome, fascinating “Magnetic Web” does similar work. Reading the illustration alongside the mechanics, the idea seems more-or-less clear; the web is integrated with the body of its user, who expectorates it to ensnare an enemy (one supposes). But the visual language gives a much more complex impression. Composed and colored like a schematic (and predating the lovely schematic art treatments of The Brothers’ War by 25 years), Rex’s image zooms us in on the visceral, bodily grodiness that the web entails.

The image indexes a concern not with function (the act of ensnaring a target) but with affordance (the very act of melding machine with body). This is not a live body, after all, but a mechanical drawing—the human form rendered like a machine both in what’s been implanted in it and by the way it’s represented on paper. The harsh sketch of the esophagus and upper jaw emphasize that this instrument is messily, perhaps violently integrated with human innards. The social problem this art hints at is one of how the human body itself changes with the integration of technology. I don’t envy the society that answers such quandaries with a Magnetic Web.

Inscrutable Instruments

If Rex’s and Garlett’s illustrations are just-barely legible, there is another class of machine that sits just beyond the horizon of our understanding. The fact of these technologies’ existence, their brute being-there, provokes a maddening conflict with the veneer of strangeness that hangs about them. They refuse to appear to us as clear, and yet they appear nonetheless.

To this category belongs Mark Tedin’s “Doubling Cube.” Floating above a jagged pit, glowing sickly green and lined with osseous ridges, the Cube hangs inscrutably in the air, no explanation offered or purpose inscribed. It pulses power in a radioactive corona; its surface is impossibly textured, etched with—something, perhaps glyphs or perhaps circuits or perhaps tiny mazes. The flavor text offers a suggestion: “The cube’s surface is pockmarked with jagged runes that seem to shift when unobserved.” Unsettlingly, the object denies sight itself.

A thousand explanations percolate in the mind, but none obtain any solidity. What being or beings made this thing? Was it unique in its power? Or, perhaps more hauntingly, was it one of many, as pedestrian to its makers as a cell phone is to us? What is this?

The cube itself offers no answers, only function: increase your mana. Take this power, if you dare.

And what if the machine on which we gaze is not a machine at all, not by our standards? The flavor text and art (another Mark Tedin) of “Dark Sphere” propses this disconcerting possibility.

I would joke that Tedin is great at painting esoteric three-dimensional shapes if the picture wasn’t so arresting as to silence my irony. Echoing the work of H.R. Geiger, Tedin foregrounds a strange organicism to this technology: it is ridged and curled like the human brain, or perhaps like the fossil of some long-dead spherical creature, or perhaps like an eldritch beast curled up sleeping. The chamber in which it’s suspended is similarly vestigial, its walls ridged like a digestive tract and the machinery below the sphere twisting like intestines. Flanking the odd device are three cloaked figures in eerie, skeletal robes. Are they there to watch it, or guard it, or draw us toward it, or warn us away from it?

The flavor text gives us a sample of what might happen when we try to touch this thing, this machine that is also alive:

“I was struck senseless for a moment, but revived when the strange curiosity I carried fell to the ground, screaming like a dying animal.”

The language, ostensibly written by one “Barl, Lord Ith” (in the Ice Age novels, Jeff Grubb misinterpreted the flavor text as a dialogue between Barl and Lord Ith), is a little difficult to parse. We’re launched right into the middle of the story (“I was struck senseless”), then progress forward (“but revived when”) and then move slightly back in time (“when the strange curiosity I carried fell to the ground”) and then linger, in a gerund, in the present “screaming like a dying animal.” The sphere, here, swirls not just with visual mystery but also linguistic confusion, a manipulation of temporal clarity. Strangest of all is the alarming final image: the cube, this object, emotes like a living creature.

The Sphere is depicted again in Tedin’s “Grip of Chaos,” whose illustration suggests that it does not uncurl like an armadillo—it is a sphere through and through. But this fact only raises more questions. In strange places and times like the one the Sphere came from, is technology the same as life? What does it sound like for a machine to scream?

Powering Down

It’s always a great joy to realize that there’s more to discover in Magic—and, indeed, that there’s more of us to discover in Magic.

In a real way, this game is made of technology. The printing press and cardboard, ink and computerization, deck boxes and playmats and language itself, all these technologies concresce into the gestalt that is Magic. What, I wonder, would these things’ metaphysical relations look like? What is the social problem they answer? And if a stranger to this world found the card called “Doubling Cube,” what would they make of it?

Thanks for the callout! Always a pleasure to read, and there's lots to chew on here. Really loved the stuff on Amy Weber's work (obviously) and that was a great close reading on Dark Sphere's flavor text. It's a doozy and some of my favorite in the game.

This was a very interesting article. I love the inspection of the more esoteric art in Magic and how some, especially early pieces, took a non-literal angle on the prompt. Early artifacts in particular do seem to best exemplify this. "Bösium Strip" by Steve Luke, Pratt's "Phyrexian Furnace", and Quinton Hoover's "Elkin Bottle" are more examples of the conceptual approach you're talking about. Hoover's painting is interesting because it has a Klein Bottle, but the twisting ribbons and frame nake it almost dissappear into the image.

I also feel there's a throughline between this article and Questioning Phelldagrif's most recent one. Some of the cards you highlighted here would function excellently in the same or similar function as Tarot cards. Even more representational cards like Dan Frazier's "Benalish Infantry" are fit for purpose, with the inclusion of swords, banners, and imagery of keys.

Also Adam Rex has a substack!